Jon Geller, D.V.M. ‘95

Once a building contractor, Dr. Jon Geller started veterinary school at the age of 41. Now an emergency veterinarian who is board-certified in canine and feline practice, he has started several emergency clinics in Northern Colorado.

Geller has turned his attention recently to helping pets of the homeless. Through his non-profit The Street Dog Coalition, he is mobilizing veterinary professionals in 20 cities to run street clinics for these pets. I sat down with Geller at his favorite coffee shop in Fort Collins to talk about the decision to go to veterinary school in his forties, the joys of ER practice, and his ideas to help homeless pets through new clinics and a cadre of volunteers.

Building a future

“I was 18 years old in 1968. Anybody that old remembers and was influenced by the counterculture movement that was so prevalent during that time. I was undirected as a youth; I didn’t know what I wanted and I wasn’t the only one that felt that way. Without specific direction, I completed two years of undergraduate coursework in education and Buddhism. Wanting to make my way West, I transferred to University of Colorado, Boulder to study alternative education.

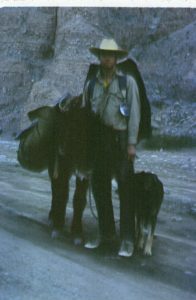

“But even the move was not enough to engage me. I dropped out of CU and drifted into the construction industry as a carpenter. At the age of 23, still in search of direction, I bought a $50 burro and trekked across the desserts of the Southwest with my German Shepherd. Those weeks were truly a journey of self-discovery, a search for more. I would highly recommend that kind of trek to any young person who feels a little lost.

“Eventually, I became a contractor, building commercial facilities and homes. I lived on a ranch near Salida with my wife and two children, traveling all over with construction and doing pretty well for myself. But when I was 38, the business side was only bringing stress. I was doing little else besides fighting with subcontractors, owners and architects over money. Simply put, I was burning out and could not see myself lasting much longer.

“I sat down and sketched out three potential career paths for myself: veterinarian, architect, or pilot. These were all based on areas in my life from which I drew a lot of passion and meaning. I was attracted to, and eventually chose, veterinary medicine because of the combination of science and healing it offered. We had lots of critters and I would help out our veterinarian when he made farm calls to our property. I admired how much of a difference our veterinarian could make in a day and how diligently he worked.”

Back to the books

“I went back to school at the age of 38 to the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, eventually completing my pre-requisites three years later, but never graduating. I applied to and entered veterinary school at 41. I moved to Fort Collins with my wife and kids, keeping an arm of my construction company going through projects in the Fort Collins area.

“In veterinary school, I was a bit of a troublemaker. Because I was older and had business experience, I could often see things that the program could improve upon. I spent a lot of time at local veterinary clinics and learned an immense amount from these practitioners. With another classmate, I designed the STEP program to help veterinary students get this real-world experience too. Unfortunately, the dean at the time pulled the plug at the last minute. But I learned that I had the capacity to impact the profession and just needed another opportunity.

“One of my most impactful rotations was equine surgery. My vision was to be a large animal veterinarian in southern Colorado, so any large animal experiences were especially meaningful. I have a very poignant memory of taking care of a retired thoroughbred who had once raced in the Kentucky Derby who was hospitalized for weeks with severe laminitis. The owners adored this horse, bringing newspaper clippings and ribbons to hang on the walls of its stall in the hospital. Everyone who walked into it knew that this horse was loved. But over the weeks, as the laminitis worsened and the horse declined clinically, the clinicians and owners began the difficult conversation about when to call it. Unfortunately, in this case, we waited too long and the horse colicked and died in a matter of hours. This decision of when to terminate care is one of the most heart-wrenching ones and a question that has shaped much of my own clinical trajectory.”

From farm to emergency room

“I graduated from CSU with my D.V.M. at the age of 45. I was very business-minded and opened up my own mixed-animal mobile practice. I cared for horses, cows, goats, camelids — anything in the Fort Collins area that needed a veterinarian. But this meant a lot of time in the truck, something that started to erode my earning potential and put me on call 24/7. Eventually, I started taking relief shifts at emergency hospitals around northern Colorado. I really connected with that type of work; I loved the shift work and the variety of cases.

“I decided to embed myself in the ER world, opening veterinary emergency clinics with my partners in Fort Collins, Longmont, Greeley, and Grand Junction. I have stayed deeply involved with the hospitals in Fort Collins and Greeley, continuing to work shifts as an emergency vet until recently. I strive to foster a family culture in these hospitals. I want a work team to become like a second family.

“At 50 years old, I became certified by the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners, which affords a specialization to treat certain species. I became certified in canine and feline practice. This was a tough certification, with requirements to write extensive case reports and take a grueling exam. I highly recommend it to those veterinarians that are interested in board certification, but find themselves in general or emergency practice. It pushes you to stay on your toes, work with other veterinarians, and mentor veterinary students.”

The anti-internship

“One of my main goals is to rework the way that internships operate for recent D.V.M. graduates. Internships in veterinary medicine are a jungle right now. Interns work long hours with a lot of cases and there is no national overseeing body for internship. However, they are often a necessary stepping stone to a residency or competitive position, especially as an emergency vet.

“At Fort Collins Veterinary Emergency and Rehabilitation Hospital, I am working with Dr. Robin VanMetre to create a sort of ‘anti-internship,’ which will provide interns with a good schedule, a reasonable number of cases, and exceptional mentorship. I hope the interns who come out of this program will prove the efficacy of this design through their clinical and interpersonal acuity.”

Homeless pets deserve care

“Another passion of mine is to help the pets of the homeless population. Back in 2014, I saw a homeless guy and his dog in Nashville sitting on a bridge. He was looking at me with no expectations, but I felt drawn to him and his dog. I started to delve into street medicine to figure out how to help others like this man. Like emergency medicine, street medicine has limited diagnostic tools. It’s fun, it’s scary, and it all depends on what resources you have.

“I founded the Street Dog Coalition, a non-profit organization that provides free care to the pets of the homeless. We mobilize volunteer veterinarians, technicians, and students through small street clinics. Without a lot of diagnostics, we use tools like taking a good history and doing a thorough physical exam, as well as bedside tests and telemedicine technologies. The medicine we can provide is mostly preventative, but we often venture into addressing acute and chronic medical issues.

“To support the clinic, we use donations of vaccines, heartworm preventative and tests, flea and tick products and other medications. We buy over-the-counter medications like Pepcid and diphenhydramine to help treat some of the more common conditions we see. We also seek grants from larger foundations to help purchase supplies as well as provide free spay-neuter vouchers.

“Homeless owners are usually great pet owners and put their pet’s health ahead of their own. They are with their pets 24/7, they will feed their pets before themselves, and they are very compliant in regards to treatment recommendations. For many, especially homeless veterans or those with a mental illness, their pets give them purpose. There is often what is called “a pack of two” mentality, where the pet and the owner are an indelible part of each other’s lives. Unfortunately, most shelters do not allow pets and those that do require a health certification from a veterinarian. This means that homeless pet owners are often limited in the services they can access. I want to help fill that gap and keep healthy pets with their owners long-term.

“Street Dog Coalition is currently in 12 cities with 8 more coming on board in the next year. I’ve learned an immense amount about non-profit management and how to match funding opportunities to the work of the coalition. I hope to encourage veterinarians, technicians, and students around the country to build in this type of community work into their practice. It is meaningful work and it puts the rest of our practice into perspective. There are about 100,000 homeless pets in the United States. If every veterinary professional gave four hours a month — or even four hours one time — the lives of those pets and their owners would be transformed.”