If you were to picture how climate change could affect horses, your mind might flash back to Hurricane Harvey, the Category 4 storm that made landfall near Corpus Christi, Texas, in 2017 and then stalled over the Houston area, dropping 52 inches of rain and causing extensive flooding. Photos and videos from news coverage showed horses swimming in floodwaters, trapped in corrals in chest-high water, or huddled together on tiny patches of high ground.

Or perhaps you’d think of the terrifying video widely shared on social media of race horses being turned loose to give them a chance to escape the wildfire that destroyed San Luis Rey Downs training center in California, also in 2017. Forty-six horses perished when the fast- moving Lilac Fire engulfed the facility before they could be evacuated from their stalls.

You might even think of the more recent severe flooding in eastern Kentucky, where 10 inches of rain fell in 24 hours in late July, washing out roads and fencing, destroying stored hay and grain, and leaving both horses and humans homeless, and worse.

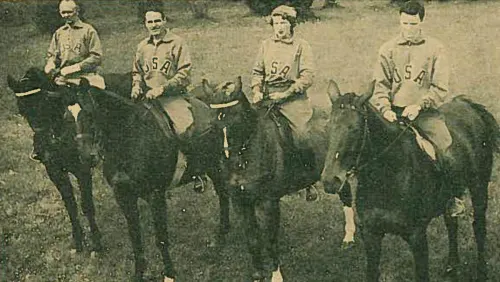

Climate change will impact every aspect of our lives with horses, and we’re only starting to see the consequences. Kimberly Loushin Photo

It’s Time To Pay Attention

The aforementioned natural disasters and others like them spurred huge responses from the horse industry to help the animals and humans affected, said Cliff Williamson, director of health and regulatory affairs for the American Horse Council, a lobbying group that represents every segment of the horse industry. But the industry hasn’t responded to the other aspects of climate change with the same intensity.

“Unfortunately, the only time we ever really see direct action around this issue is in response to natural disasters,” he said. “I’m very complimentary to the horse industry and how well they respond to natural disasters, as far as showing support for their fellow equestrians around the country, whether it’s a flood or fire or something. But as far as developing techniques to get in front of these kinds of things, I’m not seeing a lot.”

The AHC first starting having conversations about climate change with stakeholders in the industry about five to seven years ago, Williamson said, mostly around issues related to feed and hay production. But as the natural disasters started to mount, along with their major, measurable impact on the horse industry, the group’s leaders thought it was a subject they needed to address.

“We were interested in hearing how the industry would feel if we started talking about climate change, so we went in very tentatively. We issued a statement basically saying that we acknowledged that the climate was changing, and we were trying to figure out what words we could use to talk about it,” Williamson said. “And we were surprised to hear that, even though there are strong horse interests in a lot of traditionally conservative, rural areas, that people didn’t immediately jump down our throat when we started talking about the fact that the weather was changing. People were acknowledging that they could look out the window and see that weather patterns were different than they were 20 years ago.

“And so we were investigating what work was being done—research, and who was having conversations around climate change in our space. And unfortunately, there was and has continued to be very little research being done on the impacts of a changing environment around the horse industry,” he continued.

The AHC has had webinars on topics related to climate change and its effects on hay and grain production, disease patterns and issues with pests. They’ve drawn attention to sustainable farming practices and construction techniques, and they have worked with other groups that represent the interests of production livestock species to discuss the effects of federal legislation and regulatory efforts.

“But the reality is that there’s very little concrete action underway,” he said. “The feedback we get has mostly been appreciation of the raising awareness of this or initiating conversations around it. I have not seen actionable interest, which in my parlance means people investing in problem-solving activities. I have not seen an outpouring of support for funding research and what this entails, finding solutions to how this impacts us.”

It’s understandable, Williamson noted; your average horse owner is concerned about more mundane issues that seem to have more immediate impact.

“We, as a community, have a real problem with recency bias,” he said. “Climate change is not the thing that’s impacted us the most recently. It’s paying $5 a gallon at the pump. It’s my horse colicking, and the $10,000 I spent on surgery and recovery. It’s my 32-year-old donkey, from when I was a leadline kid, getting laminitis just breathing oxygen. Those are the things that have impacted me most recently, not a wildfire in somebody else’s community, not the 0.4 percent temperature increase over the last year, or the half-inch increase in water levels.”

This isn’t a problem unique to the horse industry, though, Williamson said. Although some outdoor sports industries have been more active on the issue of climate change—the ski industry in particular has been raising alarm bells—they all face the same inertia amongst their members.

“We have a monthly meeting [with other outdoor groups] where we all sit around and talk about how everything’s harder for us than it is for the next guy,” Williamson said. “The hikers and campers, they’re having the same kinds of problems. Everybody that utilizes parks is screaming into the void right now because parks are just inaccessible. We have tree die-offs; we have wildfires; we have all the other environmental issues, wildlife concerns, zoonotic disease transmissions. Ticks and parasites in general are always going to be an issue that I work on at the American Horse Council, and I never would have thought I’d find peers within the bicycling community on the same concerns. But it’s a problem now for mountain bikers because Lyme disease is everywhere, and it’s potentially killing their members. Because of temperature increases, ticks aren’t dying off in the winter like they used to, and so now you can’t go into the forest in the Northeast without coming out covered in ticks.”

Although a warming climate might not pose the same existential threat to the horse industry that it does to the ski industry, there will unquestionably be an impact, Williamson said.

“The weather patterns changing impacts everything,” he said. “Show seasons are going to start to change. If we have five years of 100 degree weather on the East Coast, starting in June and going into September, or if we just consistently have a week of over 100 degree weather at a time, people are going to stop going to horse shows. They’re going to wait for that three days where it’s nice, and they’re going to go to their local horse show instead of packing up and going to Ocala. You know, those kinds of things, you’re going to start to have an impact.”

No Feed, No Horse

The most basic level of care we provide to our horses is what they eat—the pasture, hay and grain that sustains them and provides the fuel they need for athletic pursuits, whether that’s long lazy trail rides or an Olympic show jumping round. And this is one area where everyday horse owners might already be seeing the effects of climate change on how they care for their own horses.

Corey Scott is the livestock services lead at Truterra, the sustainability division of Land O’Lakes (which also owns Purina). Although she’d never have imagined it 10 years ago, climate change and its associated effects are now one of her top priorities, not only because of the impact on hay and grain production, but because customers are starting to demand it.

“Very rarely do we see people correlating business with environmental concerns, and I think this is something that has changed significantly in the last three to five years,” she said.

The impact of a warming planet on hay and grain production can be summed up in one word: water. Either an overabundance or a lack of it.

After a major flooding event, which usually occurs in the summer, you’ll get a bloom of mosquito populations because of all the standing water. Istock/Steverts Photo

Droughts and floods have always dogged farmers, of course. But they’re now having a greater impact, Scott said.

“The extremity of [severe weather] has changed, and there’s plenty of research out there to point to that,” she said. “The extremity, and the length of time significant extreme weather patterns stick around—more prolonged drought or more prolonged wet weather as well; it goes both ways. And that’s impacting our food system significantly.”

And a big part of the food system for horses is their hay.

“Just in my personal experience, [speaking with] friends that are in the hay business here on the East Coast, on one of their rented properties they used to get 250 bales off at a time, they got 90,” said Williamson. “And that’s just because of rainfall. It’s not an annual issue, but it could be. Everybody’s rain pattern has changed, noticeably changed, in the last five to 10 years.”

Before working for the AHC, Williamson said, he was in the cattle business, and he recalls hearing from hay producers out west how excited they’d be to get a half-inch of rain.

“I’d always laugh,” he recalled. For producers on the East Coast, “That’s Tuesday! We don’t worry about having enough rain. We worry about having enough days that are dry to cut hay. For all of us on this side of the Mississippi, it’s probably [not drought] we worry about— not year in and year out. But now, we’re starting to get places where it just never really stops raining.”

ADVERTISEMENT

All of this means hay and grain are getting harder to grow in the areas where they’ve reliably been grown in the past. And—you guessed it—that means prices go up. The price of hay increased by an average of $40 per ton in the U.S. in 2021, according to Scott, and that was before the impact of inflation and rising fuel prices.

Although horse owners may just be noticing the price increases now, hay and grain producers have seen this coming and are already thinking of ways to adapt, Scott said. “It’s forcing people to look at alternative feeding methods, as well as alternative crops in areas that they wouldn’t historically look at,” she explained.

As an example, Scott cited a 2021 study from Kentucky Equine Research examining the use of cover crops in horse pastures. Cover crops are usually planted in late summer or early fall and help prevent erosion and improve the soil, but they haven’t traditionally been used in horse pastures. If employed, though, they could extend the grazing season and reduce the need for hay. The KER study evaluated annual ryegrass, winter rye, berseem clover, purple top turnip and daikon radish for nutritional content and to see which crops horses preferred.

“[The study is] a great example of how we’re needing to get creative about how we continue to grow feed and how we leverage something that we might have historically thought of as a waste crop into product,” said Scott.

“When we look at cattle feeding systems—and this has not trickled into horses yet, but I think it’s indicative of the way that we might start to think about it in horses— they have started to use those rye grasses and radishes and some of these other cover crops that really help maintain soil health and help maintain soil moisture and preventing erosion. They’re thinking of creative ways to keep them in place longer and then harvest them into feedstuff,” she added. “Now, why that’s good for us in horses is that they’re using some of these rye grasses and other forages to replace what would have historically been grass, alfalfa and other legumes that are also fed to horses.”

The livestock industry is ahead of the equine industry in facing these challenges, Scott said, partly because they’ve been under the microscope for their contributions to climate change—they’re estimated to be responsible for 12 to 15 percent of global greenhouse gas (or global GHG) emissions, she explained.

Climate change is affecting the availability—and the price—of the hay we feed our horses. Mollie Bailey Photo

“I would say it’s very different; livestock is thinking about it in a big way, because of that pressure on the food system and the role that livestock plays in that,” Scott said. “Should we [in the horse industry] be thinking about it? Yes, we should be thinking about it. Because in all the ways that we described, it’s going to have an impact on the welfare of our animals in the future, our management systems, as a whole, will see changes—how we’re feeding our animals, how we’re inoculating them, etcetera.”

The production livestock industry and the sport horse industry might seem like separate universes, with vastly differing goals and management practices, but Scott cautions that we are all in this together.

“The preservation of our partners in livestock is going to be incredibly important, not just livestock but also row crop producers, our farmers in general,” she said. “The preservation and partnership in ensuring that their operations continue in the future is critically important to horse operations. If you think about where grain is raised and where other feedstuff comes from, they are most significant partners.”

The Air We Breathe

The equine athlete’s respiratory system is a magnificent thing. It moves mind-bogglingly large quantities of air with relentless efficiency, providing the oxygen to fuel the horse’s gallop, jump or canter pirouette.

But that marvel of biological engineering is exactly why horse owners should be paying close attention to another climate change consequence: poor air quality.

This is most obvious during wildfire season, when smoke can drift hundreds of miles and affect millions of people (and animals) nowhere near the fire itself. The smoke from massive wildfires on the West Coast in the summers of 2020 and 2021 even affected air quality on the East Coast for a time.

But climate change is also going to make regular old air pollution worse. Air quality is now a hot-button topic among elite human athletes, and there’s much greater awareness of its potential to affect performance. At the elite levels of sport, when fractions of seconds matter, air quality also matters.

Colleen Duncan, DVM, Ph.D., is an associate professor of pathology at Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. Colorado has also seen an increase in wildfires in recent years, and spurred by horse owners’ concerns about their effects on air quality, as well as the impact of air quality on horses in general, she and other researchers launched the BREATHE (Better Racing and Exercise in Air That Horses Enjoy) project.

“We began by actually just asking horse owners, trainers, riders, veterinarians, other equine professionals, what they were worried about and what they saw,” Duncan explained. “Not surprisingly, people are concerned. They’re concerned about not only how [air quality] affects animals in the short term, but also whether this has long term impacts, risk factors— like, should I worry more if I have an older horse, if I have a heavy horse, if I have an allergy horse, things like that. Our goal has been to scientifically investigate those concerns and see if there is scientific evidence for that.”

After conducting a survey to determine what horse owners’ primary concerns were, the researchers began studying race horses—a group for which there is a phenomenal amount of data easily accessible. And thanks to the widespread use of air pollution monitors, many of which are near racetracks, it’s easy to determine the exact air quality at race time.

Climate change impacts everything from the ability to grow hay to the quality of the air our horses breath. Istock/MF-Guddyx Photo

“We’re looking to see if the winning times are slower for a set distance and a certain race horse type, depending on the air pollution—so, basically, if air pollution affects race performance,” Duncan said. “But I think the real story is probably much more complicated, right? We started that study based on absolutely known effects on human athletes. But we also know that it matters where you live and train. So our first pass is looking at pollution on day of, but then we’re building on that to gather, you know, what was it like when the horse was training on the track one week, two weeks, a month prior. Because that’s that repeated exposure, versus the idea was that they were only exposed on race day.”

And this gets at something that might not yet have entered the collective horse owners’ consciousness— air quality is actually something we should be worried about all the time, Duncan said. Not just on days when a wildfire in an adjacent state has caused a visible haze.

“This is a real issue with the air pollution changes that we’re seeing now—there’s a lot more small particulate matter. And that [particulate matter] actually can not only make it into the lungs, but it crosses the barrier into the bloodstream,” she explained. “The impacts of air pollution in humans, it’s just massive. They’re finding airborne pollutants crossing into the bloodstream and crossing into tissues. You can find it in the human placenta.

“So we breathe all the time, right? It’s not just the one smoke event or one bad pollution day. You are also breathing the days before that, and the days after that, and then every other bad air day that happened, if you live in a high risk zone. So it’s really this cumulative burden that probably makes the biggest difference,” she continued.

You’ve probably heard of the air quality index, or AQI, which is the Environmental Protection Agency’s index for reporting air quality. Those weather alerts you get on your phone for bad air quality are triggered when the AQI meets certain thresholds on a scale from 0 to 500: below 50 is considered good air quality, 51 to 100 is moderate, 101 to 150 is “unhealthy for sensitive groups,” and over 150 is considered unhealthy. You’ll often hear about “sensitive groups” (the elderly or those particularly sensitive to pollution, like asthmatics) needing to be more cautious, even if the air quality is good to moderate.

Air quality is even more important during exercise, because you’re breathing harder and moving more air through your lungs than you would be at rest, so professional and amateur sports have begun to take note of AQI levels as well. The National Collegiate Athletic Association recommends that outdoor activities should be shortened when the AQI is over 150, and canceled or moved inside when over 200. The National Football League, Major League Baseball, Major League Soccer and the National Women’s Soccer League all monitor AQI at game sites as well and will cancel or reschedule events when the AQI is deemed unhealthy. The U.S. Equestrian Federation recommends—but has no rule about—canceling or suspending competitions if the AQI reaches 151 or over.

Horse owners should be monitoring air quality as well, Duncan said, and considering less strenuous exercise for horses when air quality is poor. And while you can use a weather app on your phone to find your local AQI level, that’s not the whole story, she explained.

“The problem with just using AQI is it might be measured on your city hall, or on the firehouse in your community, but it might not be right at your barn. And air pollution is sort of hyperlocal, because it really depends on local wind patterns, and that kind of thing,” Duncan said.

So instead of relying on an app, Duncan recommends using personal air quality monitors. She uses a brand called PurpleAir, which allows users to share their data publicly. Their outdoor sensors start at about $260 apiece.

“For example, in our place, we have one in our indoor arena and our outdoor arena. And you will learn a ton,” Duncan said. “The really interesting thing is, your footing makes a difference, right? Dusty footing, we know that it’s a huge deal. And so you can really see [the air quality] where you’re about to exercise your horses.”

Air quality is known to have an effect on many human health conditions, and although the research hasn’t yet been done to demonstrate a similar effect on horse health, Duncan said the equine community should be working under that assumption.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The science is so solid, in humans and in laboratory animal models, that we would be ridiculously naive to not take action,” she said. “If you want to have a long [relationship] with a horse, to make it to those elite levels, that’s many, many, many years of successful training. It’s not six months of successful training. I mean, I was a Pony Club kid and desperately wanted a horse and saved every penny—you want that horse to [have a long useful life] too, right? It’s not just the Olympic athletes; it’s your best friend that you want to have for many years. It doesn’t matter what level the horse is competing at because it affects them all.”

Familiar Foes

If there’s a bit of not-so-bad news in the discussion of climate change and horse health, there’s one aspect where we actually are well prepared to deal with the effects of a changing climate—a potential increase in infectious disease. Because the primary diseases veterinarians are concerned about are covered under the core vaccines recommended to be given to every horse, we’re better armed for this aspect of the fight.

Many equine diseases—including tetanus, West Nile virus, and Eastern and Western Equine Encephalitis viruses—will become more prevalent due to various factors of climate change but are preventable with a core vaccine. Istock/People Images Photo

Sally DeNotta, DVM, Ph.D., DACVIM, is the chair of the American Association of Equine Practitioners Infectious Disease Committee and a clinical assistant professor of large animal internal medicine at the University of Florida’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

“Here in the Southeast, and actually probably in multiple places in the country, one of the primary weather patterns or natural disasters that we see increasing with climate change are increases in annual rainfall, hurricanes and massive flooding. We had floods in Death Valley this week,” she said. “Even places like Florida that are certainly not strangers to excessive floodwaters after hurricanes, we’re probably going to start seeing an increase in frequency and severity in those types of weather patterns with climate change.”

After a major flooding event, which usually occurs in the summer, you’ll get a bloom of mosquito populations because of all the standing water, DeNotta said. “Some of the more important infectious diseases to horses in this country are mosquito-borne viruses. West Nile virus and Eastern and Western Equine Encephalitis viruses all utilize mosquitoes as their primary vector for transmission. And if you have increased mosquito populations following natural disasters and flooding incidents, you’re going to have increased transmission of those viruses.”

Another overlooked risk associated with flooding events is the fact that wildlife is often displaced and is more likely to come into contact with horses.

“The more ground that is covered in water, the less room there is for raccoons and skunks and other wildlife species that we know carry rabies and parasites and other infectious diseases,” DeNotta said. “When everything gets condensed onto smaller regions of land, they have an increased risk then of interacting with dogs, cats, horses, humans, all of which are susceptible to rabies and other infectious zonotic diseases.

“The good thing about it—there is a good thing!—about mosquito-borne viruses and rabies, specifically. Those are diseases that are very preventable with the AAEP-designated core vaccines,” DeNotta added. “We can effectively prevent these diseases in horses with vaccination much more quickly than we’re going to be able to prevent climate change.”

Tetanus, also preventable with a core vaccine, is caused by bacteria found in the soil and is also an increased risk after natural disasters, DeNotta said. “Horses are more likely to get injured with either a flying projectile or something submerged in water. And they’re much more susceptible then to getting tetanus from an untreated wound in the aftermath of a natural disaster,” she said. “Natural disasters, particularly those involving heavy wind and rain and flooding, put horses at increased risk for all five of the AAEP core vaccine diseases.”

Water-borne pathogens are another concern after flooding events. Leptospirosis, a bacteria that lives in water, can infect horses and cause abortion, eye inflammation and renal failure. Pythium insidiosum, a fungus-like organism, is another concern in the Southeast, DeNotta said.

“If you’ve got standing water in backyards, in paddocks, and horses are standing in it or drinking it, they are at risk for pythiosis. If the Pythium organism gains access to the body through a small wound or an abrasion, it creates large flesh-eating lesions that are actually very hard to treat,” she said.

Pythium has also recently been found in other areas of the country outside of the Southeast, and its incidence may increase as the climate warms, which is a concern for many diseases that have traditionally been seen as regional issues.

“I think we are observing that with several insect- borne diseases, including borrelia, which causes Lyme Disease, anaplasma and other tick-borne pathogens,” DeNotta said. “As weather patterns change and different areas of the country may become more amenable to certain insect vectors, then the range of disease is going to expand right along with the vector populations. We’re already seeing a pretty dramatic expansion of tick populations here in this country.”

Another concern is anhidrosis, when a horse is unable to produce sweat. Although the disease isn’t well understood, DeNotta said, there is an environmental component related to hot, humid weather, and as more of the country starts to experience that, more horses may be diagnosed with the condition.

“There are likely horses all over the country that contain the genetic risk factors for developing anhidrosis but may not encounter the environmental triggers that they would in the Southeast,” she explained. “They sweat normally when they need to during times of exertion or hot weather, and don’t ever actually develop clinical anhidrosis. But should they come to the Southeast? That’s where environmental conditions lead to an impaired sweating response that can really make the condition much more obvious.”

If there’s a consistent theme that runs through discussions of the threats of climate change, it’s that regional issues may suddenly become national, and that’s one of DeNotta’s biggest concerns—that horse owners may not anticipate the new types of threats they could face and might not be prepared.

“In upstate New York, I was there 10 years, I don’t know that I ever saw a document for horse owners about how to shelter in place, how to prepare to evacuate a horse and what you actually need to do that safely. Whereas in Florida, we have lots of resources like that. So it might just be that the states that have been more prone to natural disasters in the past just need to share their resources more widely,” she said.

DeNotta is originally from Oregon and said a heat wave in 2021 pushed the temperature in Portland to an unheard-of 115 degrees. “My family in Oregon, they’ve never had to handle 115 degree weather [with their horses],” she said. “So I was trying to counsel them on, you know, you need to go out, and you need to hose the horses down every hour, and I helped them set up some misters—where you can hook a hose up to an ongoing sprinkler system, essentially so that they can they can get access to misters. But growing up in Oregon, there was no need to have a horse mister! It never got that hot.

“So [it’s] making people aware [of] planning for shade, cooling, cool fresh water for the horses to drink, ability to rinse them off. It might just be that the tips and tricks used in the hot parts of the country just need to be shared with the rest of the country.”

In the last decade or so, the AAEP has gotten increasingly involved in disaster response, as well as in providing informational resources to horse owners to prepare them for potential disasters.

“There has been more information published in the last five years about how best to respond to an incident in the [equine] media than there was before,” said the AHC’s Williamson. “How to respond to a fire, how to respond to a flood, how to respond to an ice event, whatever.

“AAEP and their staff have really stepped up in the last five to 10 years in regards to what their response to natural disaster looks like, and how those responses need to persist year round,” he added. “AAEP has been at the forefront of that. Any information you’re going to find about how to respond to a natural disaster is going to be based off of the AAEP.”

And that information has never been more important, for everyone, DeNotta stressed.

“I really recommend that people even more seriously consider, if I needed to pick up and evacuate with my horse—due to a fire, or a hurricane, or a flood—am I ready to do that? And do I have a plan in place? I think having a plan in place is so critically important for any disaster preparedness, for the humans and animals. Owners knowing where shelters might be around their state. Having a working trailer that is kept in good condition, having horses that are trained to load—some things are really simple,” she said. “Making sure your horses are always up to date on vaccines, you have good documentation with current Coggins, you know how to get health certificates should you have to leave the state. Those types of small preventative measures throughout the year will make it so much easier for you to pick up and get out of the danger zone when the time comes.”

This article ran in The Chronicle of the Horse in our Sept. 5-19, 2022, Issue. Subscribers may choose online access to a digital version or a print subscription or both, and they will also receive our lifestyle publication, Untacked.

If you’re just following COTH online, you’re missing so much great unique content. Each print issue of the Chronicle is full of in-depth competition news, fascinating features, probing looks at issues within the sports of hunter/jumper, eventing and dressage, and stunning photography.