CULTURE KEEPER

Navajo veterinarian delivers education and livestock medical services for her tribe

By Coleman Cornelius | Jan. 3, 2022

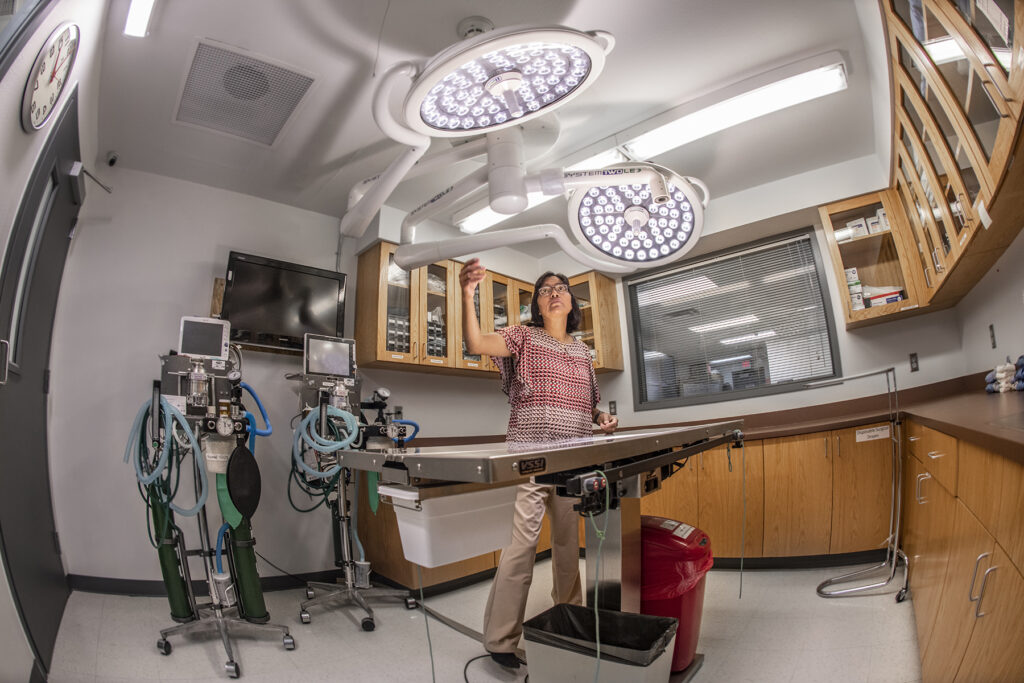

DR. GERMAINE DAYE PULLED ON her green coveralls and boots in the Veterinary Teaching Hospital at Navajo Technical University, set in Crownpoint, New Mexico, and surrounded by stunning rock formations and mesas. At that moment in August, a mare with a nasty hindquarter laceration was being trailered in for follow-up treatment, and 13 rams in the university flock were waiting in a corral for vaccinations and hoof-trimming.

Before moving to those demands, Daye appraised a whiteboard, where notes summarized the year’s single biggest veterinary project on the eastern side of the Navajo Nation. In July, Daye and a team of students had cared for 1,735 sheep and goats owned by 58 Navajo elders. The veterinary team had traveled from one isolated high-desert community to another – from Church Rock to Coyote Canyon to Lake Valley – to deliver free preventive livestock medicine. They conducted physical exams, gave vaccinations, administered drugs to control worms and other parasites, and collected fecal samples to screen for infectious disease. In many cases, the flocks included just a dozen or so animals. Yet, those sheep and goats are a vital source of food and fiber for their older Navajo owners.

So, in caring for the animals, Daye was also nurturing her culture. It’s a responsibility she tirelessly carries out at the Navajo Nation’s Veterinary Teaching Hospital, with hope for the future as her fuel.

Here, Daye is a practicing veterinarian – one of just three based on the Navajo Nation, which spans 27,000 square miles in the Four Corners region of New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona. Calling this a region with a veterinary shortage is a serious understatement. Daye also directs food and agriculture courses and runs the only accredited veterinary technology program at a Tribal university in the United States. This year, her leadership responsibilities will expand further, when she launches a bachelor’s degree program in animal science.

The new program will make Navajo Technical University the only Tribal university with animal science and veterinary technology programs running side by side. Together, the academic programs will prepare students for careers related to livestock production and veterinary medicine. These are critical needs on the Navajo reservation, where many families rely on small livestock herds for food, including ceremonial meals, and for fiber used to weave blankets and rugs, an important cultural tradition and source of income.

“Seeing how much she works – she’s busy 24-7 – it motivates me,” said Hunter Livingston, who is studying with Daye to become a licensed veterinary technician.

A flock of sheep raised at the Navajo Technical University’s Veterinary Teaching Hospital is used for training students in the school’s vet tech program. Rams in the flock also are sold and leased to producers on the Navajo Nation, which helps ranchers improve flock genetics and supports the Navajo culture. Photography: Lance Cheung / U.S. Department of Agriculture

IN FACT, MOTIVATING HER STUDENTS is Daye’s primary professional goal. She was one of three children whose single mother insisted her kids go to college. Daye attended Colorado College in Colorado Springs with scholarship support, then earned her veterinary degree at Colorado State University in 2001. After several years of private practice, Daye returned to her homeland and started work at Navajo Technical University in 2009. She lives with her husband and young children outside Crownpoint, where she grew up horseback riding and tending cattle and sheep on a landscape studded with piñon, rabbitbrush, and sage. Her grandfather was born in a stone hogan in their backyard.

“The only way we can become a better nation and have a better economy and come out of poverty is through education,” Daye said. “We’ve got to look to education to survive and maintain who we are. It’s the way we will move forward as a society. My goal is to help as many students as we can.”

The task at hand was teaching two of her vet tech students to inject vaccines and trim the hooves of Rambouillet rams that soon would be leased to Navajo sheep producers for the breeding season. The lease program is another significant outreach project for Daye and the university’s Veterinary Teaching Hospital: Each year, the program allows two dozen Navajo sheep producers to use rams they might not otherwise be able to afford, while also improving their flock genetics.

“Let’s bring one out,” Daye instructed the students and two staff members helping with the rams, whose fleece filled the air with an aroma of lanolin in the hot sun. The animals were lined up in a paneled alleyway to be weighed, then handled one at a time. The woolly fellow next in line was a stout 285 pounds, and the crew led him out by halter.

Now, Livingston would learn to administer a vaccine to protect the ram against several strains of bacteria that can cause fatal illness in sheep. Daye explained the subcutaneous injection method as she handed Livingston a loaded syringe. “You’re going to pull that skin out, and you’re going to keep the needle parallel to the body,” Daye instructed, showing her student the technique on the ram’s neck. She wore kneepads over her coveralls, knowing she would be spending much of the next two hours kneeling in a corral working on struggling sheep. “You’re making a tent with the skin,” Daye explained. “Watch your fingers in case the needle pierces through the other side. Then just go under the skin and push the plunger. Try to be quick about it.”

She was tentative, but after several moments Livingston managed to inoculate the sheep. “That was scary,” she admitted.

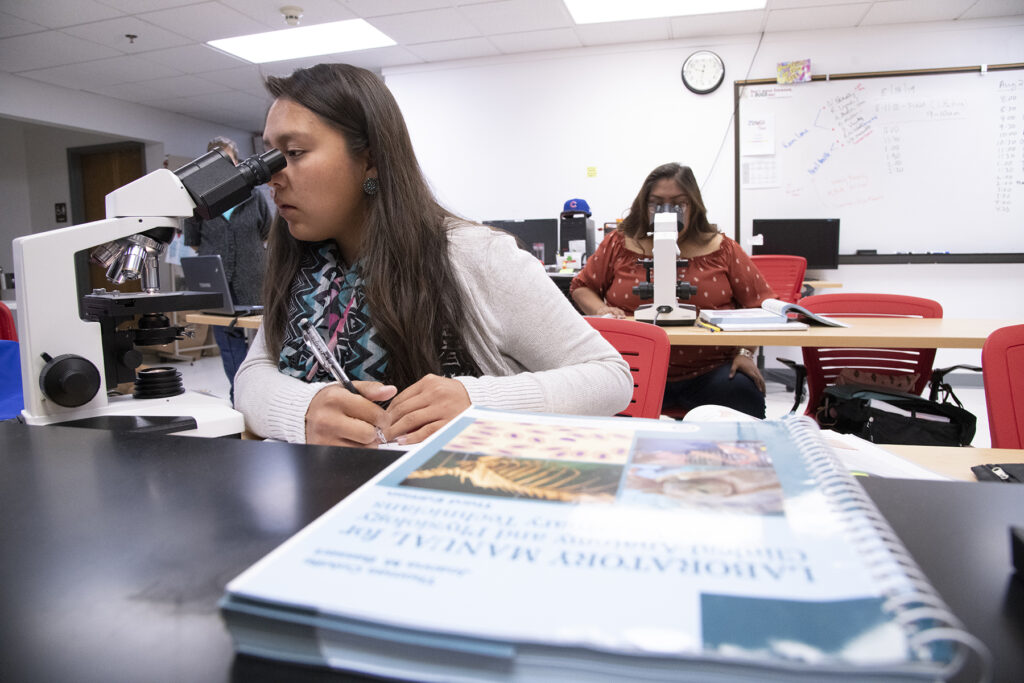

Livingston, 21, grew up in Gallup, not far from Crownpoint, and is working toward an associate’s degree in veterinary technology. Through Daye’s efforts, the program at Navajo Technical University is allied with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. The partnership provides eight-week internships for Navajo vet tech students, and Livingston completed one last summer in Lexington, Kentucky, where she helped with health checks for horses held in quarantine after being transported from abroad.

Now, she would learn to trim sheep hooves with handheld shears, much like pruning shears for the garden. “We want to stay flush with the sole,” Daye instructed her student, as she demonstrated on a 202-pound ram. The trimming would help the rams avoid lameness as they trod rugged terrain. “I will bevel the toe just a little bit. You see that? Now the outer lateral claw is done.”

Nearby, student Morgan Yazzie, 23, worked with a program instructor on a different ram. Yazzie, in her second year of the vet tech program, was already confident giving vaccinations and trimming hooves. She, too, completed a USDA summer internship. Yazzie was in Augusta, Maine, where she helped agency veterinarians capture raccoons and draw blood to monitor for rabies.

Her internship, coupled with learning alongside Daye, has inspired Yazzie to set her sights on vet school, with the hope of eventually practicing on the reservation. “Dr. Daye made me have that interest, that motivation, that knowledge. She made me strong,” Yazzie said. “I think about it a lot.”

The tribal university generally graduates two or three students in the veterinary technology program each year, Daye said. She hopes as many as 20 students will annually earn bachelor’s degrees in the new animal science program when it is fully up and running.

Dr. Germaine Daye, at left, is director of the Navajo Technical University Veterinary Teaching Hospital. The hospital is one of just a handful of veterinary clinics serving the vast Navajo Nation. At right, Morgan Yazzie, foreground, and Jeandria Mariano are among students in the university’s veterinary technology program. Photography: Lance Cheung / U.S. Department of Agriculture

Dr. Germaine Daye, top, is director of the Navajo Technical University Veterinary Teaching Hospital. The hospital is one of just a handful of veterinary clinics serving the vast Navajo Nation. Bottom: Morgan Yazzie, foreground, and Jeandria Mariano are among students in the university’s veterinary technology program. Photography: Lance Cheung / U.S. Department of Agriculture

DAYE IS STARTING THE PROGRAM with about $440,000 in grants from the USDA. The funds allowed her to renovate a modular building and to equip the space with teaching supplies and furnishings. Also purchased with grant money, a new tractor, sheds, and an array of equipment stood at the ready to handle school and client animals.

As Daye surveyed the new facilities, she envisioned training more students – and having more helpers for community outreach programs. In addition to the flock health and ram lease programs, Daye leads an equine health project each spring, when she and students provide preventive care for up to 300 horses over several days at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital. She also runs a steady stream of community workshops and K-12 programs to share information about topics including gardening, livestock, and companion animal health.

During community programs, Daye often speaks Diné, the Navajo language, especially with older tribal members who are fluent. She encourages her students to do the same as a way to enrich themselves and their culture.

“To serve this area of the Navajo Nation is important to me,” Daye said. “There’s just so much we can do.”

Photo at top: Dr. Germaine Daye is a veterinarian and associate professor at Navajo Technical University in northwestern New Mexico. She oversees the school’s veterinary technology program and is establishing its animal science program, making hers the only tribal university with both programs. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has partnered with Daye to provide grant funding and internships to support her teaching programs and students. Photo: Lance Cheung / U.S. Department of Agriculture

SHARE