An epidemiologist drives through a blizzard to interview victims of an outbreak. A veterinarian advises a rural family on the disease dangers of raising feral swine. Virologists collect bats in Ugandan caves and mosquitos in Thailand. A public health official investigates a COVID-19 outbreak in a skilled nursing facility.

These are disease detectives at work. They are our first line of defense against infectious disease outbreaks. Disease detectives work at the intersection of science, medicine, and public health. They may fight any source of infectious disease at any scale, from a county outbreak to a global pandemic, but they are all united in their adaptability, their curiosity, and their dedication to saving lives.

Kathy Benedict

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

In 2015, Kathy Benedict deployed to Sierra Leone during the largest Ebola outbreak in history. A few months later, she was in Wisconsin to investigate an Elizabethkingia outbreak. Elizabethkingia is a bacterium commonly found in the environment that rarely causes disease in people, but this outbreak included a cluster of 65 illnesses and 20 deaths in a tristate area.

“I was driving around Wisconsin in February in the snow to interview patients, to learn about their exposures, and figure out exactly what they had in common so we could identify the source of the outbreak,” Benedict says. “In my experience, if they’ve experienced illness, they also want to know what caused it. So, part of the interviews can be not just gathering information but also sharing information and helping them understand. They want to protect the people they love and make sure that they don’t have the same issue.”

After completing dual degrees in epidemiology and veterinary medicine, Benedict (Ph.D., ’11; D.V.M., ’13) joined the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service so she could get hands-on training in outbreak investigation. The EIS is a two-year fellowship program in applied epidemiology at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s widely considered the country’s flagship program for preparing disease detectives to investigate public health threats in the field.

Benedict is now a veterinary epidemiologist in CDC’s Outbreak Response and Prevention Branch, where she focuses on diarrheal diseases such as salmonella, E. coli, and listeria. Benedict no longer gets middle-of-the-night calls to fly to snowy Wisconsin, but her team monitors enteric zoonoses through a national surveillance system that can alert them to multistate outbreaks of genetically related illnesses linked to animal contact. Once alerted, CDC works with state and federal partners to coordinate investigations, communications, and other actions.

“The job requires a ton of flexibility in terms of responding to what’s needed right now, from collecting very simple information to very complicated analyses, where you need to pull together disparate types of data and make solid conclusions based on that data,” Benedict says. “You have to be willing to wear lots of different hats.”

You also have to deal with disappointments. Benedict wants to find answers so she can prevent disease, but investigations can lead to dead ends.

“We didn’t solve that Elizabethkingia outbreak, and that’s never a great feeling,” Benedict says. “Ultimately, the illnesses did stop, but we never identified the issue. When you’re an EIS officer, you want to be part of the solution, but in reality, you don’t always come to that final conclusion.”

Unsolved problems keep Benedict excited about her work. “There’s always something new. It’s a forever-student learning opportunity.”

Kyran Cadmus

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Veterinary epidemiologist Kyran Cadmus also embraces adaptability and surprises.

“We will work with anything,” Cadmus says. Any species, any disease, any outbreak.

50 diseases, and the list keeps growing,” Cadmus says.

As a field service officer for the USDA, Cadmus (D.V.M., ’10) responds to any suspected cases on the list of notifiable animal diseases maintained by the CDC and the USDA. “That’s about 50 diseases, and the list keeps growing,” Cadmus says.

Cadmus manages surveillance programs in Colorado and, as part of an incident management team, she responds to larger outbreaks anywhere in the United States and even overseas. In the past year, she’s worked on tilapia lake virus and pseudorabies in Colorado, virulent Newcastle disease in California, bont ticks in the U.S. Virgin Islands, and African swine fever in the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

“Every outbreak starts at the local level with either the field office or private veterinarians who send samples to a lab. If the lab gets a positive for a notifiable disease, they’re obligated to send it to our national veterinary services labs for confirmation. And then lots of telephones start ringing,” Cadmus says. “If it’s early in the outbreak, it’s a lot of trying to wrangle data and understand what we’re defining as a positive premise. My job on the team is to say, ‘Yes, this location is positive. We need to take action here.’ It can be kind of chaotic while figuring out how big the response needs to be and what needs to happen.”

Cadmus has knocked on doors in Compton to interview residents about their backyard poultry. She has necropsied tilapia at aquaculture farms. She has helped wildlife services confiscate and test feral swine, all with the goal of figuring out where a disease came from and where it’s going next so the USDA and CDC can control its spread.

“This is One Health,” Cadmus says. “We make sure that we have adequate healthy livestock to eat so that people aren’t interacting with wildlife species and picking up diseases from them.”

In other words, Cadmus works every day to prevent the emergence of new zoonotic diseases like COVID-19. In her words: “I’ve always been attracted to big-picture medicine. Things that can help more than just one animal at a time. I’m helping animal populations and human populations. It’s truly public health.”

Darci Smith

U.S. Department of Defense

Darci Smith (B.S., ’02) decided to become a virologist during the 1995 Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. “I just couldn’t believe that something so small could be so devastating,” Smith says.

Smith was still in high school, and her family couldn’t afford college tuition, so she attended Colorado State University on an ROTC scholarship, and then received her Ph.D. before going on to active duty in the Army. Smith may have joined the military to pay for her education, but she connected so deeply with the mission that she has served for 20 years. Smith is a civilian microbiologist at the Naval Medical Research Center and a reservist for the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases.

“In the military, we’re a family and we all take care of each other. I want to take care of my family, so I want to understand what diseases might pose threats to military personnel,” Smith says. “The pandemic has really highlighted the potential impact of infectious diseases on operational readiness.”

Department of Defense personnel are stationed all over the world where they can encounter rare, emergent, and weaponized pathogens. The DoD’s biodefense efforts rely on three core capacities: surveillance, investigation, and medical countermeasures such as vaccines and therapies.

Chikungunya virus is an excellent example of a pathogen that concerns the DoD. The mosquito-borne RNA virus causes debilitating fever and joint pain. The disease is endemic to Africa and Asia, but since 2004 it has spread to more than 60 countries and was imported to Europe and the Americas by infected travelers. In 2009, Smith was on active duty in the Army when she had her first field experience surveilling for chikungunya virus during an outbreak in Thailand. Smith also worked in the field in Azerbaijan and the Republic of Georgia, where she taught local scientists how to survey for mosquito- and tick-borne diseases.

“Capacity-building is an important part of our work. Anytime we’re going to another country, we’re working with local scientists to help them become proficient in surveillance,” Smith says.

Today, Smith works in a BSL-3 lab at Fort Detrick in Maryland. Early in the pandemic, her team began receiving SARS-CoV-2 clinical samples. “People were positive for long periods of time with the PCR tests, and they couldn’t come out of quarantine and perform their jobs until they had a negative test. The military needed to know how long people might be shedding infectious virus,” Smith says. Eventually, it became clear that the infectious period lasts only about 10 days. Now, her lab is studying variants and breakthrough infections and developing assays. Her research group has produced nine assays for the Navy’s COVID-19 field surveillance.

“I’ve been in this field for over 20 years, and this brand-new virus comes along and we’re learning basic things about it,” Smith says. “That’s what keeps me in this field. There’s so much to learn, so many different viruses, and they’re all so different in so many ways.”

Anna Fagre

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

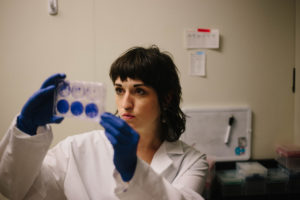

Anna Fagre works at the interface of wildlife health, environmental health, and human health. Her passion is using data to illustrate the natural history or ecology of a virus. Fagre wants to know: “Who is the virus infecting in nature? How is it circulating? Which arthropods are being infected? Who are the arthropods biting? Which wildlife hosts are being infected and helping to amplify that virus in nature? Which species are getting the virus from its wild cycle into human populations?”

Anna Fagre works at the interface of wildlife health, environmental health, and human health. Her passion is using data to illustrate the natural history or ecology of a virus. Fagre wants to know: “Who is the virus infecting in nature? How is it circulating? Which arthropods are being infected? Who are the arthropods biting? Which wildlife hosts are being infected and helping to amplify that virus in nature? Which species are getting the virus from its wild cycle into human populations?”

When Fagre (M.P.H., ’12; D.V.M., ’15; Ph.D., ’21) joined the Epidemic Intelligence Service in 2021, she realized a dream she’d been pursuing for a decade. Fagre applied twice and completed degrees in public health, veterinary medicine, and infectious disease microbiology before she was accepted into the highly competitive program, all so she could work in the field.

Fagre is “nerding out” over the natural history of an arbovirus in her first boots-on-the-ground experience as an EIS officer. She’s evaluating a statewide disease surveillance system from data collection to analysis to dissemination. “I get to help a state evaluate their mosquito surveillance program to make sure that they’re collecting the right type of mosquitos, using the right type of traps, testing enough mosquitos, and learning enough on an annual basis to help protect public health.”

Fagre’s laboratory background is the ideal foundation for applied epidemiology. “It’s really awesome to think about outbreaks from the hospital bed to the lab to the cloud server for data analysis by our big-data people. Being able to feed that swab you take from an individual into a larger picture helps paint the portrait of what’s going on at a national or global scale.”

Fagre calls this approach to infectious diseases “swab-to-sequence.” It’s the public health equivalent of farm-to-fork thinking.

Justin Lee

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

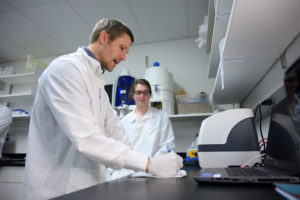

Swab-to-sequence public health is possible because of Justin Lee (Ph.D., ’13; D.V.M., ’15) and his team at the CDC’s Genomic Sequencing Laboratory in Atlanta. At CSU, Lee studied infectious diseases in bobcats and mountain lions. He learned to appreciate the complexity and challenges of fieldwork during trips to Colorado’s Uncompahgre Plateau to capture wildcats. He also discovered a talent for genomics that he now uses to support disease surveillance and research from across the country.

Before COVID-19, the Genomic Sequencing Laboratory processed 10,000 to 12,000 samples per year from the entire range and scope of the CDC’s mission. Now, it’s the primary lab for the National SARS-CoV-2 Strain Surveillance program. Last year, Lee’s team processed more than 40,000 samples from all over the United States and its territories. Their data is integrated with data from other sources and made available online so the public can view changes in the genetic diversity of COVID-19 over time.

“Our surveillance efforts certainly monitor the comings and goings of variants, but we are really focused at a finer level on the mutations within the variant that affect things such as diagnostic testing or therapeutic options,” Lee says. In other words, Lee’s lab creates a detailed picture of the virus’s genome and how it’s changing over time so his colleagues can characterize how the virus’s behavior will change as it mutates.

“Ultimately, what we want to know is the public health impact of these mutations. Not just what mutations are present, but what do we need to know about them, and what do we need to do about them?” Lee says.

The average person now discusses omicron and delta like thrillers they’ve read, but those are just the titles on the spine. Lee and his colleagues are writing the text inside, only as soon as they close one variant book, there’s a new one to fill in. “Delta came as a single form and by the time omicron took over, there were over 100 identified sub-lineages of delta,” Lee says.

Lee is surprisingly optimistic about this burden.

“One of the most exciting things that has come out of the devastation that has been COVID-19 is a massive investment in sequencing capacity across the country and around the world for public health,” he says. “In the 12 months between the emergence of alpha and omicron, a lot of money, organization, and structure were put into the system. More sequencing is happening in a distributed fashion now, so the U.S. sequencing capacity has gone up as a whole. There are so many areas where this is going to benefit public health down the road.”

Rebecca Hermann

Boulder County Public Health

CDC employees such as Benedict, Fagre, and Lee all depend on local disease detectives such as Rebecca Hermann to do their jobs. Hermann (B.S., B.A., ’17) is an epidemiologist at Boulder County Public Health where she plays an essential role in Colorado’s pandemic response.

Hermann studied environmental health and Spanish at CSU and completed a Fulbright scholarship in Colombia. She was studying infectious diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and planning a research career in neglected tropical diseases of Latin America when the pandemic changed her trajectory.

Hermann returned to her home in Colorado to finish her degree online. She began working as a part-time contact tracer and case investigator and, after earning her master’s degree, she became a full-time epidemiologist. Hermann now works on outbreaks in business and health care settings, from gathering data and identifying outbreaks to providing guidance and monitoring the situation.

“In a weird silver-lining way, I have gotten exposure to what it’s like to work at the local level in public health, and it’s been so eye-opening,” Hermann says. “It’s changed my perspective about where I thought I fit into the system of public health.”

Hermann became passionate about health equity while living in South America, but the pandemic has brought that passion home. “I feel like COVID has laid bare for all of us a problem that already existed, which is that the populations who are most strongly impacted by infectious disease tend to be more marginalized and have less access to health services,” Hermann says. “I hope that it sheds a light on how underfunded our public health system is, not just in the U.S. but globally, and how critical it is to have those surveillance systems in place and have a strong public health workforce.”

Hermann says that her colleagues are the best part of her job. “They genuinely want to help their communities and make a difference. They will go above and beyond. They will stay late and start early. They’re deeply empathetic, which is a double-edged sword.” Hermann worries about the toll the pandemic is taking on the public health workforce, particularly when it comes to science hesitancy.

“How do we combat misinformation and disinformation? How do we build trust with people in public health? Some of these misinformation campaigns are incredibly effective and they’re killing people. So how do we as public health actively confront that head-on? I think that’s been a real challenge.”

It’s never an open-and-shut case

Misinformation and science hesitancy are just two of the challenges to our public health system that have been underscored by the pandemic. These disease detectives all worry about the intersectional problem of health equity, surveillance, and data.

Benedict believes a health equity lens is essential to preventing disease. “Are we collecting the right information about at-risk populations to help us understand what diseases are present in these populations? How do we communicate to at-risk populations to make sure that we’re closing any disparities between populations of people?”

Outdated surveillance and data systems need to be modernized. At the same time, marginalized populations have to be represented in the public health workforce. “I hope that we can recruit diverse young people into public health and bring in and support underrepresented groups in the sciences,” Lee says.

Climate change is another looming crisis in public health and infectious diseases. New pathogens are emerging as a result of climate change, and old pathogens may become more problematic or virulent. “Our lack of understanding of how climate change impacts disease processes keeps me up at night,” Fagre says.

Unfortunately, with pathogens old and new, we don’t know what we don’t know.

Fagre and colleagues at the CDC are working on big data. They are collecting and analyzing historical data sets so they can contextualize changes in diseases over time. If they can understand how climate change impacts infectious diseases, then maybe they can “disrupt the cycle” before another pandemic begins.