By Sarah Ryan

Photos by Kellen Bakovich

Edith Silvas Villalobos never met a conversation she didn’t like.

Silvas, the diversity, equity, and inclusion coordinator for Colorado State University’s One Health Institute, lives at the intersection of many identities. She is a Latina social justice activist with a master’s degree in divinity who considers connecting with others and letter writing her ministry. Silvas brings all those identities to the table as she works to make science and higher education more diverse, equitable, and inclusive one relationship at a time.

“Value, dignity, and respect are the pillars of my work,” Silvas says.

Family sticks together in sickness and in health

Silvas grew up in Texas in a large, extended Mexican-American family. Her parents picked cotton, and her father was a migrant worker. None of her grandparents had the opportunity to attend high school, yet both of her parents earned graduate degrees, and they expected their three children – Edith, Denis, and Daniel – to attend college as well. Her mother often told them: “Never forget you are the children of educated cotton pickers.”

Faith was as important as education and literacy in the Silvas family. “I learned every person has value,” Silvas says. “Every living thing has value, and we are stewards of the environment. We don’t own it.”

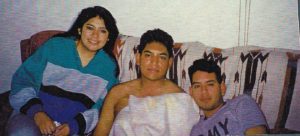

The family’s faith was tested when her middle brother, Denis, was diagnosed with an aggressive osteosarcoma at the age of 23. Denis was covered under his parents’ health insurance, but after he lost his leg to bone cancer, their HMO refused to cover his surgery. Denis, a veteran, transferred to the nearest VA hospital to avoid interruption of care.

Two years later, Denis passed away after the cancer metastasized to his lungs, but his family never stopped fighting for justice. His parents considered litigation, but did not want to drag the family through a difficult court case. Instead, they settled for mediation with his physician and testified before a Texas Senate committee. Their testimony helped lead to health care reforms in Texas three years after Denis passed away.

Silvas was Denis’s primary caregiver during his last year, and it changed her life’s direction. For nearly a year, Silvas was “silenced” by her family’s loss. She never returned to her career in advertising. She stopped leaving the house or seeing friends. She was in deep mourning.

Eventually, Silvas felt called to work for change within the same health care system that had failed her brother.

From silence to service in health care

Silvas worked for justice and equity in health care for nearly twenty years. She researched systemic barriers to health care and provided resources and services to communities with limited access to care. For example, at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, she implemented and managed the mobile mammography program that provided breast cancer education and mammography services for uninsured and underinsured women.

Trust and curiosity were essential to breaking down barriers. Silvas met with managers in the city’s health clinics to understand the services they offered, the gaps in care, and their patients’ needs. Then, she went into the community.

“We talked to schools, libraries, and churches,” Silvas says. “They needed to know they could trust us. Like what happens if this test comes back and I need more tests? What happens if I have cancer?”

Silvas learned to build authentic relationships with the communities they sought to serve. “Respect, trust, and honor, they take time to build,” she says. “They’re not given automatically.”

While working at MD Anderson, Silvas volunteered every Thursday night in the pediatric oncology ward. She spent those evenings with teenagers who were fighting cancer. They talked about music, played video games, and cooked dinner together. She was “bowled over” by the pedi ward’s chaplain.

“The way that he walked with the patients and their families was incredible,” she remembers. “He cared for the families with so much love, and the staff that worked on that floor. I thought, when I grow up, I want to be like him.”

Then, Silvas did an internship at a hospital in Mexico. She helped a physician and a nurse check on the promotoras (community health workers) who were trained to provide basic health services in rural communities that lacked running water and access to health care. As she encountered pudor (shame) about women’s bodies, Silvas became interested in how theology informs health and medicine. She asked: “How do you work with faith communities to facilitate these conversations?”

For Silvas, the answer was through education. Silvas decided to pursue a Master of Divinity so she could engage in those conversations on an equal footing with a priest or pastor. She earned her Master of Divinity from Andover Newton Theological School (now Andover Newton Seminary at Yale Divinity School) in 2006, but friends call her an MDiva (instead of an M.Div.) because she is a Latina Minister of Celebration.

Crucial conversations about diversity and equity

At CSU’s One Health Institute, Silvas helps scientists think systematically about diversity, equity, inclusion, and social justice. She also raises public awareness of the One Health approach, which works to advance the health of humans, animals, and the environment.

For example, the National Science Foundation awarded $12.5 million to an interdisciplinary team of CSU researchers to study how airborne microbial communities – the aerobiome – impact health. “We all have to breathe,” Silvas says. “And the quality of that air is tied to health equity or lack of it.”

Silvas builds the institute’s relationships with communities that are traditionally marginalized by science and medicine. As part of the aerobiome grant, she is working on programming to recruit and retain underrepresented and first-generation students in science.

For the program to succeed, they have to rigorously interrogate the academic system. “How welcome do these students feel at CSU? If they’re not a part of it, they won’t stay,” Silvas says. This proactive approach to recruiting and retaining diverse students is quietly revolutionary.

The church of conversation

On a sunny Saturday morning, Silvas sits at her kitchen table and writes letters. Dozens of cards and letters she has received are pinned to a Mexican wrought iron rack on a nearby wall. She will try to respond to every one of them in careful, beautiful handwriting.

“I never wanted to be a pastor,” she said. “This is my ministry.”

Like any true ministry, it never ends. When Silvas returns from a trip, she tries to write letters to everyone she met while she was away. When she receives an answer, she writes back as soon as she can. She believes deeply in the power of the written word and human connection, and the importance of including different people, voices, and culture in her work and her ministry.

Silvas’ motto sums it up: Cada cabeza es un mundo.*

*Loosely translates to “every mind contains its own world.”