The head and the heart

How does mental health affect the body?By Jessica Cox

Illustration by Billy Babb

Brent Myers began his research journey with a simple question: How does the brain regulate mood?

He still hasn’t answered that question but has since learned that the brain seems to impact much more than mood alone. With the help of a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and additional funding from the National Institutes of Health, Myers is building his understanding of the physiological and behavioral effects of chronic stress, transforming one simple question into several more complex ones along the way.

Hurting the heart

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide, but while maintaining a “heart healthy” life typically means making diet and exercise adjustments, depression is actually a bigger risk for cardiac death than cholesterol; in fact, it doubles a person’s risk of having a heart attack.

Understanding why and how prolonged psychosocial stress, including mood and anxiety disorders, increases risk for chronic physiological illnesses like hypertension and diabetes is at the heart of Myers’s research.

“We’re trying to understand, from top-down in the brain, how does this work?” Myers said. “How do negative or even positive mood states from the brain affect an individual’s health throughout their entire body?”

While physiological illness may be a relatively recently discovered outcome of prolonged stress, one of its more well-known impacts is amotivation, often in the form of social withdrawal. A healthy person seeks out social interaction because it’s inherently rewarding.

While monitoring brain activity, Myers and his team are able to observe the differences in social behavior of animals who have been exposed to chronic stress versus those who haven’t. When presented with a novel social environment, the brain of an animal with a history of stress responds – but only at first. Once the novelty of the situation wears off, the brain no longer generates neural activity during the behavior.

“There seems to be something that chronic stress is doing to the brain to reduce the neural representation of social behavior,” Myers said. “Which could probably drive a lot of social avoidance after chronic stress.”

Stopping the spiral

When an activity like socialization is no longer rewarding, motivation to engage in that activity in the first place is hard to come by, ultimately reinforcing cyclical behaviors of social withdrawal and amotivation.

“Because the more withdrawn and amotivated you are, the less rewarding your life is, the more stressful it is and the more stressed you feel, the less motivated you are socially – so it becomes a downward spiral,” Myers said.

According to Myers, this is why a lot of depressive and anxiety-like illnesses can become so cyclic and chronic, life-course type illnesses. They change the brain to make the disease state more likely to happen, causing a self-reinforcing pattern of behavior.

“If we can understand those initial neural changes that are creating the negative motivational state and the decrease in sociability, we can intervene before that spiral starts,” Myers said. “But once that spiral starts, it is difficult for cognitive reframing or words from friends to make something that’s unpleasant, pleasant.”

Tyler Wallace, a biomedical sciences Ph.D. candidate in Myers’s lab, can relate. After experiencing a personal loss in 2015, Wallace recognized depressive behaviors in himself and family members, which is part of why he chose to pursue a degree with a focus on biological research. Making a consistent effort to adapt to life with loss, Wallace is often reminded of one of the not-so-obvious fundamentals of how the brain works.

“Some people expect our brains to go on forever, but the brain is a biological thing that gets tired and needs upkeep, just like a muscle,” Wallace said. “Something that I’ve taken away for myself and for family members is to take care of your brain with healthy food and exercise, and ‘be nice to yourself.’”

While Wallace gained some encouragement from understanding the basics of the brain, not everyone is able to subvert the spiral of depression as effectively.

It sounds pretty bleak, but Myers is hopeful that there’s no “point of no return,” and even a person in the depths of depression can find their way back by activating new neural pathways. Treatments like deep brain stimulation and ketamine injections hold promise for helping reset neural activity to allow for improved quality of life.

Mapping the mind

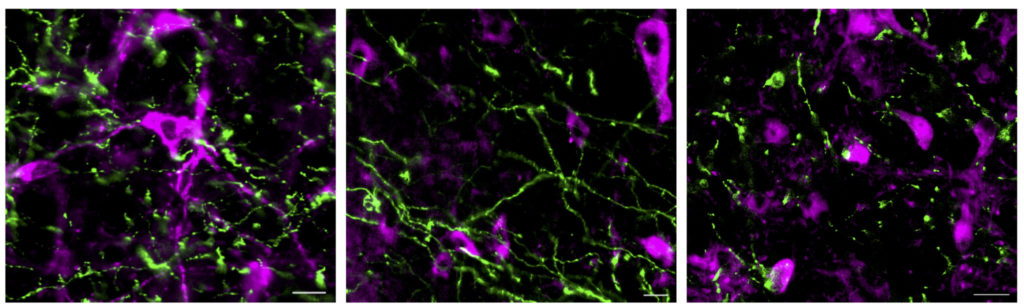

Using animal models, Myers maps brain activity to help build the bigger picture of how specific cells and cell groups in the prefrontal cortex respond to stress-relevant stimuli like motivation, reward, and sociability.

The prefrontal cortex is tied to our mood and emotional state, so these cells don’t directly alter behavior, nor do they directly cause physiological changes like an increase in blood pressure. But because they’re part of an interconnected network of cells within the body, activating brain cells can cause a chain reaction of additional responses that, somewhere along the way, results in physiological effects.

Using a mapping technique called optogenetics, Wallace can see in real time how different neurons within a brain region control social interaction. Observing these responses helps build an understanding of how certain brain regions, which we already know contribute to the development of mental health diseases like depression, also regulate cardiovascular function.

“When it comes to mental health, we’re learning how important excitation versus inhibition is in certain brain regions,” Wallace said. “Sometimes it’s easy to think the more neural activity, the better, but an emerging pattern is the importance of balance.”

By identifying the specific cells that govern stress responses, including how those responses somehow trigger a subsequent physiological response, Myers hopes to be able to target specific conditions for potential treatment. For example, while selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) are a common medication used to treat depression, they don’t help with the stress-related consequences on the cardiovascular system. Other drugs can cause unintended and undesired side effects on seemingly unrelated systems while treating depression or anxiety, too.

“A lot of medications have very global effects, so it becomes hard to treat one manifestation without side effects on another system,” Myers said. “The more we can fine tune a specific neuromolecular basis for each feature of these disorders, the better chance we have of targeting one system without the off-target effects on another.”

Following the chain of neurotransmission

While Myers began with observing activity taking place in the prefrontal cortex, he plans to follow the chain of responses caused by this initial brain activity to gain a better understanding of what happens next in the process.

By monitoring and modulating projections coming from the prefrontal cortex and to other areas of the brain, like the hypothalamus or the brainstem, Myers and his team can then observe how behavior and physiology are affected when these projections are either stimulated or inhibited.

Every road leads somewhere, and mapping out the individual steps of the neurotransmission process may lead to behavioral and physiological changes that relate to depression, anxiety, hypertension, and diabetes – and hopefully an answer to how and why those changes are happening.