Marielle Gerard, a former blackjack dealer and dressage teacher, knew that Joker was the one when she watched him run. Gerard fell in love with him as a 5-week-old pinto Dutch Warmblood with knees the size of dinner plates, she knew he would be huge and “he had the most beautiful gaits to make a super dressage horse,” she says.

Gerard purchased Joker in 2013, shortly after she survived breast cancer. Joker, at five months old, developed an abnormal gait. Dr. Steve Long, her veterinarian, told Gerard that something was a little off with Joker.

Long suggested that Joker go in for some X-rays to see what was wrong. They determined that his spinal column was pinched, signs of a neurological condition known as Cervical Vertebral Compressive Myelopathy (CVCM) or Wobbler’s disease.

In 2014, Gerard took Joker to the James L. Voss Veterinary Teaching Hospital at Colorado State University to be the first Wobbler patient as a part of a new study headed by Dr. Yvette Nout-Lomas, associate professor in equine medicine at CSU.

“The idea is that the horse has clinical signs that make them look neurologic. And we call that ataxic, which essentially means uncoordinated,” says Nout-Lomas. “It’s a developmental disease, the bony canal in which the spinal cord runs is essentially too narrow at certain spots. And where it’s narrowed, it’s going to compress the spinal cord,” she says.

The role of the spinal cord is to communicate information from the brain to the body and from the body back to the brain, and so if there is damage at the level of the neck, it is going to create problems affecting the front and back legs, according to Nout-Lomas.

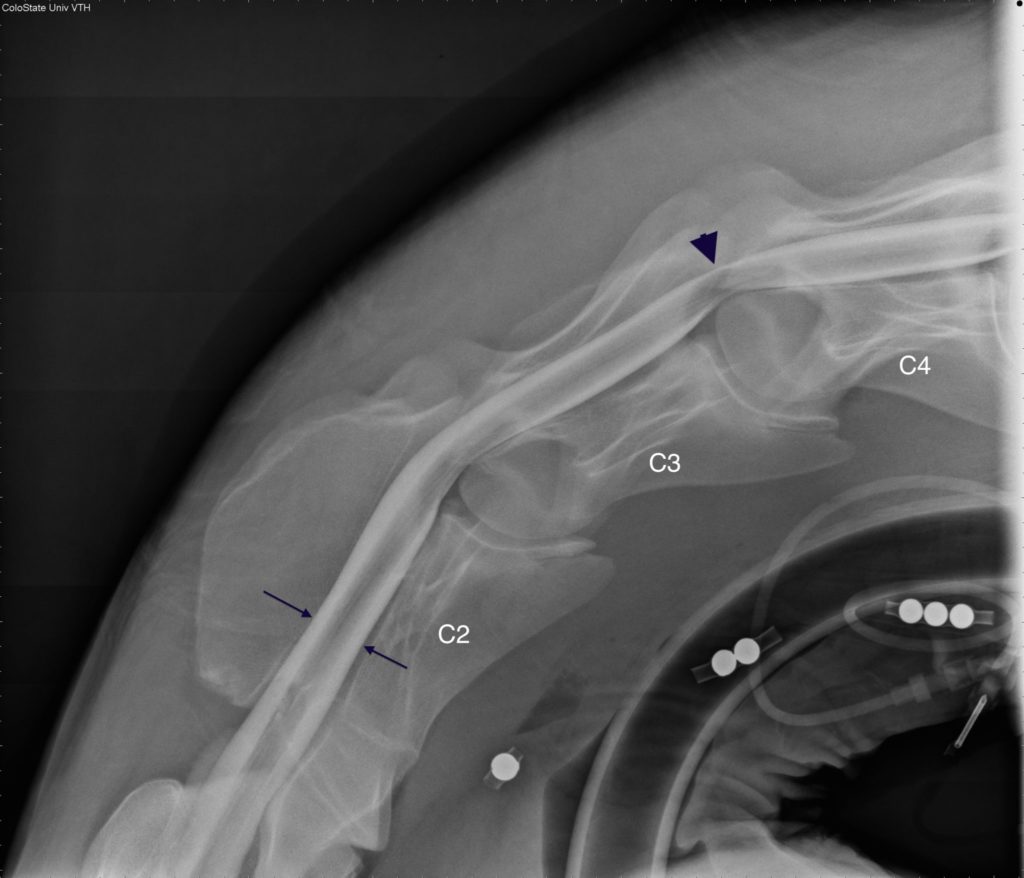

Gerard took her 16-month-old Joker to CSU for a myelogram, which would provide an official diagnosis. A myelogram happens under general anesthesia, where contrast is put around the spinal cord, and then sites of compression will show up on the radiographs.

“We can manipulate the neck, flex it, extend it, and look for those sites of compression. If you have a site of compression, you have a diagnosis of a Wobbler or CVCM,” says Nout-Lomas.

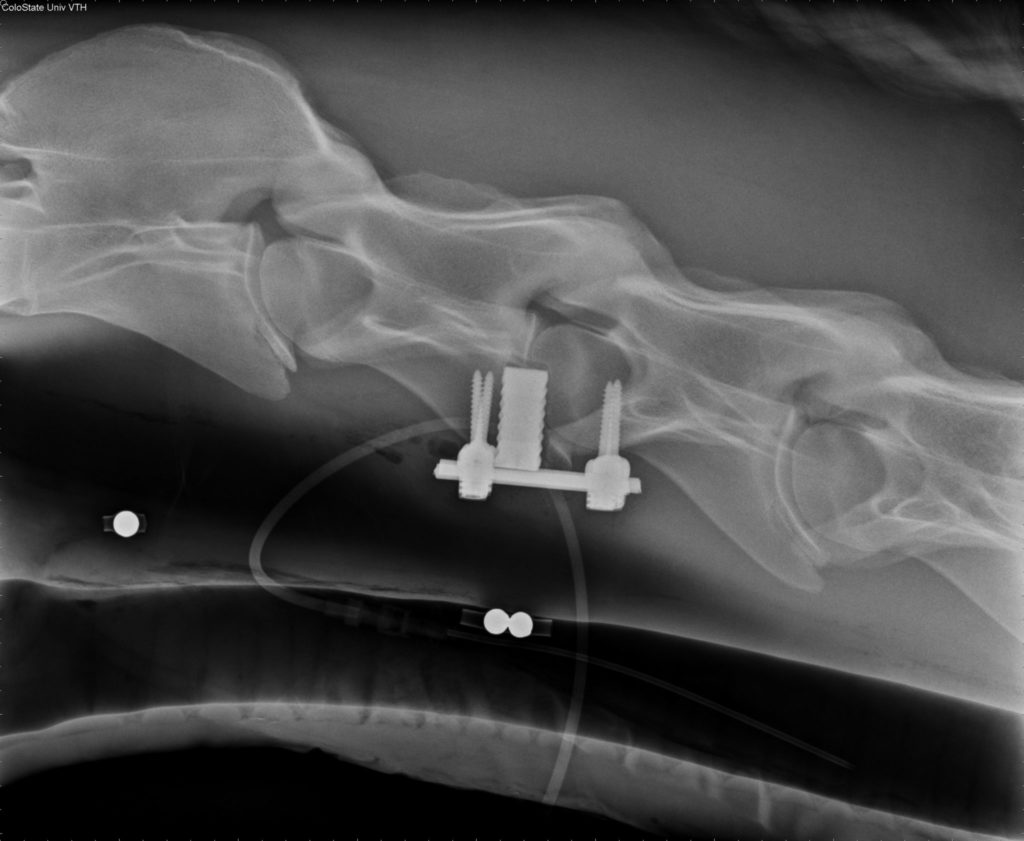

A few weeks after the official diagnosis, Dr. Jeremiah Easley, equine surgeon at CSU, performed Joker’s surgery which fused two vertebral bodies to create more space for the spinal cord.

“The thought process is that by reducing movement at the junction of two vertebral bodies, reduces the volume taken up by tissues that are no longer needed in that area, thereby leaving more space for the spinal cord,” Nout-Lomas says.

CSU is one of three places in the United States that can surgically treat horses with Wobbler’s, and one of the only places internationally as well. Most horses with Wobbler’s are euthanized partly due to a lack of access to treatment, as well as potential complications following the treatment.

“In the equine world, surgery is not necessarily enthusiastically received by many people, because people worry about the fact that there’s always going to be some damage that you cannot repair,” Nout-Lomas says. Most horse owners would most likely pay for a new horse, rather than pay the same amount for an operation that would risk complications and prevent riding and dressage competitions.

But Gerard is dedicated to Joker and was not concerned with riding or dressage. She was willing to give Joker a chance without being caught up in a particular outcome.

Joker’s surgery was successful, “he did not develop a lot of the complications that we’ve seen in some of the subsequent horses,” says Nout-Lomas. She kept Joker in the hospital for about a week after “because he was the first [patient], I wanted to make sure he didn’t have problems, but his neck healed very nicely,” she says.

“I parked my camping chair outside his stall, no one told me I had to leave, so I basically was there with him from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. every day,” says Gerard.

Being one of the few veterinarians in the world with the resources and expertise to treat CVCM, Nout-Lomas focuses her research on finding out why the disease happens, what the causes are and reducing the development of them.

Nout-Lomas also wants to improve the outcomes for those affected. And she hopes that the uncertainty of the outcome can be changed to make treatment more reliable beneficial.

Joker is 8 years old now, and according to Gerard, the surgery saved his life. “If he had not had the surgery, he’d be dead, yes, I lost my all-time biggest dressage horse I was ever going to have, but this horse has brought me so much pleasure,” she says.

He runs and plays; his recovery has been remarkable. “I’ve never regretted it [treatment]. I’m sad that he ended up going through what he’s gone through, but now I can get up and ride him,” she says.