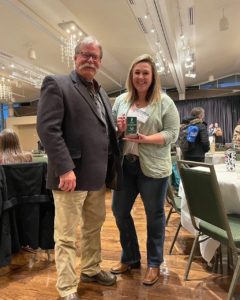

Biomedical Sciences PhD student Jessica Kincade was awarded first place in the Enteric Diseases of Food Animals awards category at the Conference of Research Workers in Animal Diseases, and second place in the Outstanding Oral Presentation in Advances Stage Basic Research category at CVMBS Research Day for her work studying fetal bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) infections and postnatal epigenetic dysregulation with Traubert Professor Thomas Hansen, director of the Animal Reproduction and Biotechnology Laboratory.

This novel research could help the cattle industry develop better management techniques, therapeutics, and improved vaccines in the future.

Kincade is a United States Department of Agriculture National Needs Fellow, a program that aims to train the next generation of policy makers, researchers, and educators in the fields of food and agricultural sciences. She earned a master’s degree in reproductive biology from the University of Missouri before coming to CSU.

“I was interested in studying immunology and also wanted to continue studying reproduction and the Animal Reproduction and Biotechnology Laboratory at CSU is one of the only places in the country that puts both of those together,” says Kincade.

A costly virus

BVD is a widespread virus among cattle herds around the world and costs the industry around $1.5 to $2.5 billion every year. The majority of this loss is due to the virus causing decreased conception rates and increased stillbirths, as well as the production of calves that have been infected in utero.

When BVD infections occur in healthy adult cattle, their symptoms are usually mild, but they may experience decreased milk production, weight loss, and immunosuppression that can lead to secondary infections.

“When pregnant cattle get BVD, the mother is usually fine, but the calf can be significantly impacted,” says Kincade. “And the outcome depends on how early or late in gestation the infection occurs.”

When born, cattle that were infected early in utero never fully clear the virus and potentially expose any other animal they come into contact with throughout their lives. “These persistently infected cattle are generally immunosuppressed, so they really don’t do well,” says Kincade.

Calves infected later in gestation, however, are able to clear the virus as their immune systems are more fully developed. Kincade and Hansen wanted to better understand the different ways cattle are impacted throughout their lives after contracting BVD during different points of gestation in utero.

“We wanted to see, if this is happening in utero, is it creating damage that is never really repaired?” says Kincade.

They found that even when infected later in gestation, cattle exposed to BVD in utero are drastically underweight throughout their lives and experience other lifelong defects in bone, brain, heart, and immune system development.

Going forward, Kincade and Hansen plan to continue conducting more sophisticated data analysis as well as further studying how these calves respond to other pathogens.

“We have many more questions,” says Kincade. “This is something that has not been investigated enough and we want to know the extent of these epigenetic differences. We have high hopes and a lot more work to do—I am very excited to be part of it.”