BMS PhD student Hayley Templeton was awarded first place in the Advanced-Stage Translational Research category at CVMBS Research Day for her work studying intestinal neuroimmune involvement in Parkinson’s disease development with Professor Stuart Tobet.

The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease, a neurodegenerative disorder of the brain, has doubled in the past 25 years. “There is currently no cure for Parkinson’s disease,” says Templeton. “There are only treatments for symptoms that can become ineffective over time.”

Templeton earned a bachelor’s degree in biology and psychology and a master’s degree in biomedical sciences from CSU before taking some time away from school to teach anatomy and physiology at Front Range Community College. “I loved teaching and that is why I decided to come back to CSU for my PhD,” says Templeton. “I want to teach at the college level.”

Templeton is researching aspects of whether the gut could potentially be playing an important role in the development of Parkinson’s disease and hopes the work could help lead to more targeted and improved therapeutic treatments in the future.

The gut-brain connection

“Your gut actually has more neurons in it than your spinal cord,” says Templeton. “It connects to your brain via the vagus nerve and is sometimes referred to as the second brain.”

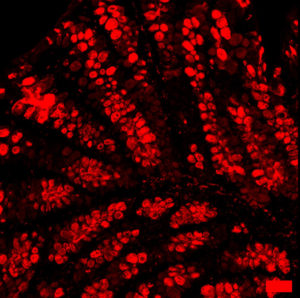

Templeton’s project involves looking at potential ways the gut could be the origin of the development of Parkinson’s disease in certain populations by studying the impact of the pesticide rotenone on gut cells as well as immune and neural responses. In particular, she is looking for an increase in a protein called alpha-synuclein, which is a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease. This protein typically accumulates in a misfolded way in the brain during the disease, which is thought to lead to the disease’s characteristic motor symptoms of rigidity and slowness.

“I am still in the preliminary stages of this work because there are so many different cell types and immune cells,” Templeton says. “I am looking to see which ones look different, how they are different, and what is causing them to be different.”

Templeton’s preliminary findings show potential disruptions to the gut’s barrier, which is important for preventing harmful pathogens and toxins from entering the body. Next, she also plans to see if sex differences are apparent and also to explore connections to leaky gut syndrome.

“There is a great deal of interesting research showing how much is tied to the gut—from mood and behavior issues to neurodegenerative disorders,” says Templeton. “It is exciting to be in a field that is gaining so much attention and to be involved in translational research, it feels like I can really make a direct impact.”