By Rhea Maze

Photos by Chase Baker

Studying chronic stress can get heavy. Perhaps as an unintended consequence of their work, the students in Brent Myers’s lab maintain a steady stream of jokes and contagious laughter, which science has long shown to be a powerful stress reliever.

Over the past year, three of its members earned predoctoral fellowships to support their leading-edge work studying impacts of chronic stress: Biomedical sciences Ph.D. student Derek Schaeuble from the American Heart Association; Research Associate and biomedical sciences Ph.D. student Sebastian Pace from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and D.V.M. and Ph.D. combined degree program student Carley Dearing from the National Institutes of Health.

“These are very competitive grants and it is rare for students to get them, let alone three from one lab in one year,” said Myers, an assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences. “It makes me incredibly proud and happy for them because it opens a lot of doors in their careers and will help them reach their goals.”

While better understanding impacts of chronic stress is the unifying theme of each lab member’s work, their projects are distinct.

“Our lab runs large, intensive studies and everyone jumps in at different points to make it all work so there’s a lot of teamwork,” Myers said. “Everyone is aware of what each member of the lab is working on and openly shares their experiences and strengths to help one another.”

Keeping it light

In the Myers lab, a little laughter goes a long way.

“We have a lot of lighthearted humor with each other all the time,” Schaeuble said. “Being able to be open with everyone else in the lab and discuss things freely has been really good development for a scientific career.”

“We have great communication in the lab and are always involved in one another’s experiments,” Pace said.

“We’re a team,” Dearing said. “None of us is doing a project truly by ourselves, we are all always there to help each other. One of the main reasons I joined this lab was because the support network is so strong—and because we’re always cracking jokes and I just like everyone so much.”

Other members of the tight-knit Myers lab include biomedical sciences Ph.D. student Tyler Wallace, Research Associate Carlie McCartney and neuroscience junior Ema Lukinic.

While Schaeuble, Pace and Dearing conducted much of the work for their fellowship grant applications when in-person campus activities were paused due to the pandemic, they managed to stay connected and met up for virtual game nights.

“Seeing them push through the grant process during the pandemic, which meant a lot of virtual meetings with me at home while my kids were out of school and we were all trying to make it work, really showed their perseverance,” Myers said.

Discoveries that matter now more than ever to a stressed-out world

Two years into the global pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that 38 percent of adults in the U.S. experienced symptoms of anxiety or depression from April 2020 through February 2021, compared to 11 percent in 2019.

“We won’t know for years what exactly all of the consequences from the stress we have experienced during the pandemic are going to be,” Myers said. “But it’s clear that these are problems we are not getting away from—stress levels are not going down.”

And stress impacts everyone. Since the National Institutes of Health implemented a guideline in 2016 that requires both sexes to be studied in scientific research, it has finally become easier for Myers’s team and other labs to expand the scope of their work.

“Everything in clinical medicine has previously been based on a 70kg male,” Myers said. Due to this imbalance, most adverse drug side effects impact females.

“Once we were able to start looking at how the work we had been doing in males applies to females, we found that everything was different,” Myers said. “We do not see anything that is the same when we look at brain circuit control of behavior and physiological outcomes after chronic stress between males and females—it is totally different.”

In their stress models, Myers’s lab tends to see that males show more cardiac consequences of stress and females show more metabolic consequences. “For example, when males go through chronic stress their hearts get bigger and that doesn’t happen to females,” Myers said. “And when females go through chronic stress they have problems with glucose and metabolism and that doesn’t happen to males.”

The three students’ fellowships will help uncover key answers to why these differences occur and more, with Schaeuble and Dearing’s work looking at some of the female-specific outcomes, and Pace’s work exploring both differences and similarities.

“These fellowships lay out a path forward for the projects we are going to do throughout the rest of our Ph.D. work and provides support to do it,” Pace said. “And working closely with our mentors and committee members throughout the process will help us develop into better scientists.”

The lab ‘chef’

“Stress is something people experience on a daily basis and how it can physiologically affect us is really interesting,” Schaeuble said.

He got hooked on neuroscience research as an undergraduate student and is looking at how exposure to chronic stress can lead to cardiovascular disease.

“We think there is brain circuitry involved that malfunctions when exposed to chronic stress and leads to elevated stress responses and over-activation of the heart,” Shaeuble said.

Dubbed the lab’s ‘chef,’ Schaeuble is a talented cook and recharges by being physically active.

“My girlfriend and I got a puppy right before the pandemic and then unexpectedly adopted another dog, so training them has become a new hobby for me,” Schaeuble said. “And after a long day of science I have to get out and do things like run and play basketball.”

After graduating, Schaeuble hopes to gain a few years of work experience in areas that interest him before deciding on a long-term career goal.

The lab ‘dad’

“The pandemic has definitely made this research area more relevant,” Pace said. “Everyone is experiencing more stressors and it is valuable to be able to communicate about it now more than ever.”

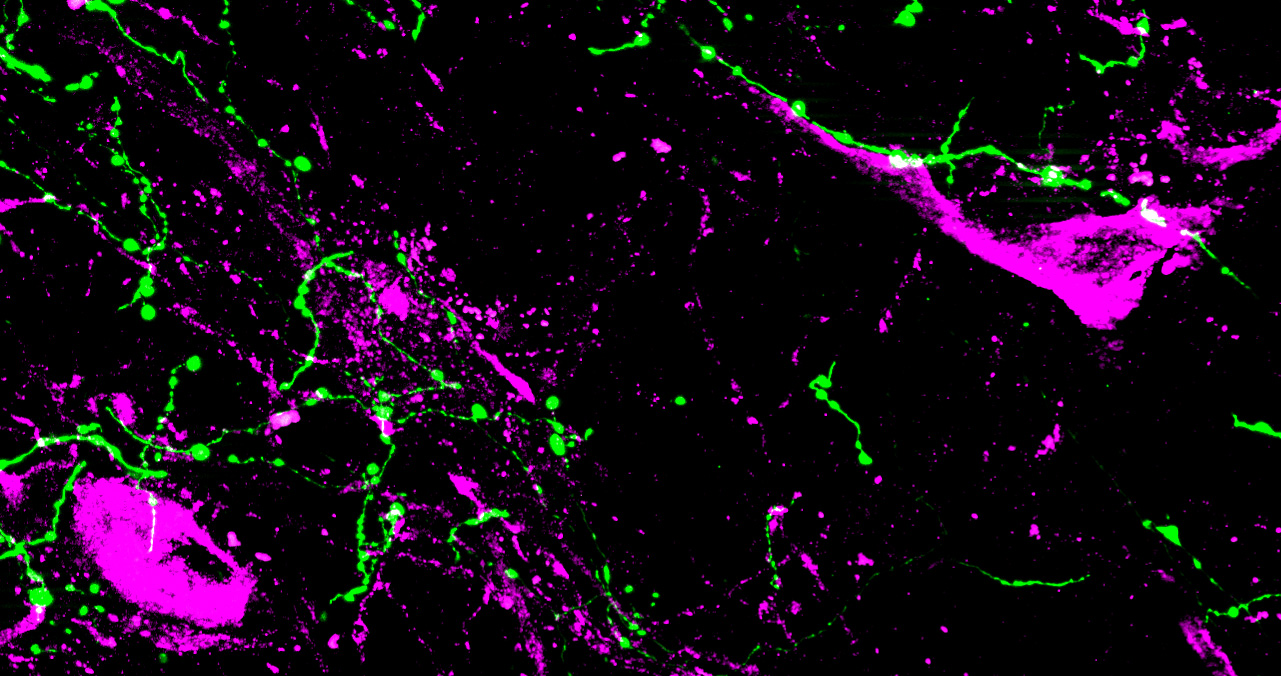

Pace completed his undergraduate and master’s degrees in biological sciences at the University of Texas El Paso and decided to pursue research after taking an endocrinology class. In 2017, he joined Myers’s lab as a research associate and lab manager and later began the Ph.D. program. His project builds off a serendipitous discovery in the lab that showed that a pathway exists from the brain’s cortex directly into the most basic survival area of the brainstem, where breathing and heart rate is regulated—which goes against current long-held theories.

Pace is now focused on looking at chronic stress effects in this circuit and how it might regulate the cardiovascular system. “It was not part of the original plan, but it has turned out to be really fruitful,” he said.

Pace, lovingly called the ‘dad’ of the lab, is who everyone goes to with questions first. He also has a three-year-old son who he loves to play outside with.

“I enjoy dad life,” Pace says.

He spends as much time as he can with his family in both Colorado and El Paso and hopes to continue to pursue a career in neuroscience research.

The lab’s ‘determined one’

“We live in a world where there’s a lot of stress,” Dearing said. “And often we trivialize it by saying things like ‘oh, I’m so stressed at school and work and I’m not sleeping well.’ But it is really important for researchers to show the drastic impacts stress can have on health.”

Dearing earned undergraduate and master’s degrees in biology from the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology before enrolling in the D.V.M./Ph.D. dual degree program at CSU and joining Myers’s lab. Support from the Medical Scientist Training Program helped her write the grant for her fellowship.

Dearing’s project expands on findings she previously published that showed that after experiencing chronic stress, females have problems with glucose control. She is looking at the same cortex-to-brainstem circuit as Pace is, but will be focusing on the regulation of glucose and how, under chronic stress, it can change in females.

Jokingly named the lab’s ‘determined one’ for her ability to juggle the intense demands of the dual degree program, Dearing has precious little free time. She unwinds by going biking with her husband, baking, and reading science fiction or fantasy novels to give her eyes and brain a break.

“I fell back into reading books during the pandemic as a way to counteract having so many virtual meetings” Dearing said.

After completing the dual degree program, Dearing hopes to become a veterinary neurosurgeon and continue doing research.

“I love both worlds,” Dearing says. “I hope I can make a difference on the broader translational level as well as on a more intimate clinical day-to-day basis.”