By Seleta Nothnagel

Blue was a day-old hatchling picked from a bin of chicks at the local feed store. I developed quite a bond with Blue early on and began taking her on trips to the pet store and the hardware store. She seemed to enjoy our outings and even developed quite a fan base within the community.

She’s a Blue Splash Marans, known for their calm demeanor, and she became a house chicken after several fights with her mean-girl flockmates. In the house with us, her personality really began to shine: she would torment the cats, crow when we didn‘t give her enough attention, and made contented purring noises as she sat in my lap.

In early 2020, I noticed that 2-year-old Blue didn’t seem like herself anymore. Instead, she seemed to be doing a lot of lying around. She became insecure about jumping on and off things, instead coming and pecking at my leg to indicate she wanted to be picked up or by making soft, melancholic noises at my feet.

She stopped crowing and purring when I petted her, and she didn’t want me to hold her anymore. With only the slightest bit of stress or activity, she started panting with her beak open, and her comb and wattles turned from a bright red to a deep purplish-blue color, a condition called cyanosis.

Going places with me and meeting people became too stressful for Blue, and as she sat in my lap in the car, she would lay her head on my arm limply and go to sleep. She developed pressure sores over her breastbone and put on weight from lying around so much. She began making strange squeaking noises as she breathed and normal activities like dust bathing made her tired. When she ate or drank, she choked, struggling to coordinate the act of swallowing and breathing.

A diagnostic odyssey

I took her to vets across the Front Range. She had countless radiographs, ultrasounds, and blood draws to determine the cause of her exercise intolerance and cyanosis.

Out of the numerous tests came just as many theories as to what might be causing her symptoms: upper respiratory infection, heart disease, heart failure, obesity, blocked nasal passages, cancerous mass in her abdomen?

We tried antibiotics, diuretics, heart medications, and a diet and exercise program where we did repetitions of wing flapping or running across the yard for a small treat. Nothing worked.

Finally, after a visit to the Avian, Exotic and Zoological Medicine service at the CSU James L. Voss Veterinary Teaching Hospital, and a CT scan, we had an answer: a PDA (patent ductus arteriosus), which is a connection between the vessels of the heart that deliver oxygenated blood to the body and the vessels that deliver unoxygenated blood to the lungs. This opening is normal in a developing embryo, and closes before hatching. However, a PDA that does not close on its own allows oxygenated blood and unoxygenated blood to mix, increasing the workload on the heart and lungs.

“Our service prides itself on offering the highest quality medicine regardless of the species. We know about the snickers and comments, and I hope that people are able to recognize how the human animal bond exists for ANY species.” -Dr. Matt Johnston

Essentially, I had two treatment options: take her home and keep her comfortable until it was time to send her over the rainbow bridge or forge ahead into the unknown and hope that it could be surgically repaired.

This surgery had never been done on a bird before, and the anatomy of the chicken made it even more difficult to achieve a successful repair. I could easily lose her on the table, but if we didn’t try, I would eventually lose her to heart failure.

I knew I would be devastated if I lost her during surgery, but at least I would be assured of three things:

1) An entire team of skilled veterinarians would learn something that day about poultry medicine and the human-animal bond that may help someone else down the road.

2) I gave her a chance most people would not have had the care, courage, or financial means to give.

3) That never was there any ounce of my love and devotion I did not give my beautiful girl Blue!

I know, you think I’m nuts

About 17 years ago, I worked at an emergency veterinary clinic in Longmont. One night, I took a call from a woman in the wee hours of the morning who wanted to know if we would see chickens. A fox had gotten into her coop and killed some of her birds, and left three that needed stitches.

I rattled off the standard fare about our emergency fee ($65 per bird back then), our location, etc. and hung up. I thought that this had been a prank call, and the whole team got a huge chuckle out of the phone call and we all agreed that she would likely not show up.

Lo and behold, about an hour later, here came this woman with her three hens. We ended up sewing up all three and her bill was around $500. Not once did she balk at the cost, she just wanted us to fix her birds.

Behind closed doors, we all joked about how it would have been much cheaper to put them in a pot for dinner. (You might be thinking that now.)

I chuckled about someone spending $500 back then, but between vet visits, diagnostics, surgery ($4,000, same as for a dog or cat) and medications, we have spent a little over $10,000 on Blue’s care.

A first in veterinary medicine

I was very impressed with the amount of research and legwork the CSU team did to prepare for the surgery, which took place Nov. 10 in the hospital’s Pocket Foundation Hybrid Cardiac Interventional Suite, unique in veterinary medicine. The anesthesia team – Dr. Khursheed Mama and technician Ellen Shaub – made sure Blue was comfortable and pain-free. Exotic medicine intern Dr. Zack Dvornicky-Raymond managed our case, spending many hours with me, organizing meetings with cardiology, and scouring the literature for similar cases. He is writing up Blue’s case for publication in a scientific journal.

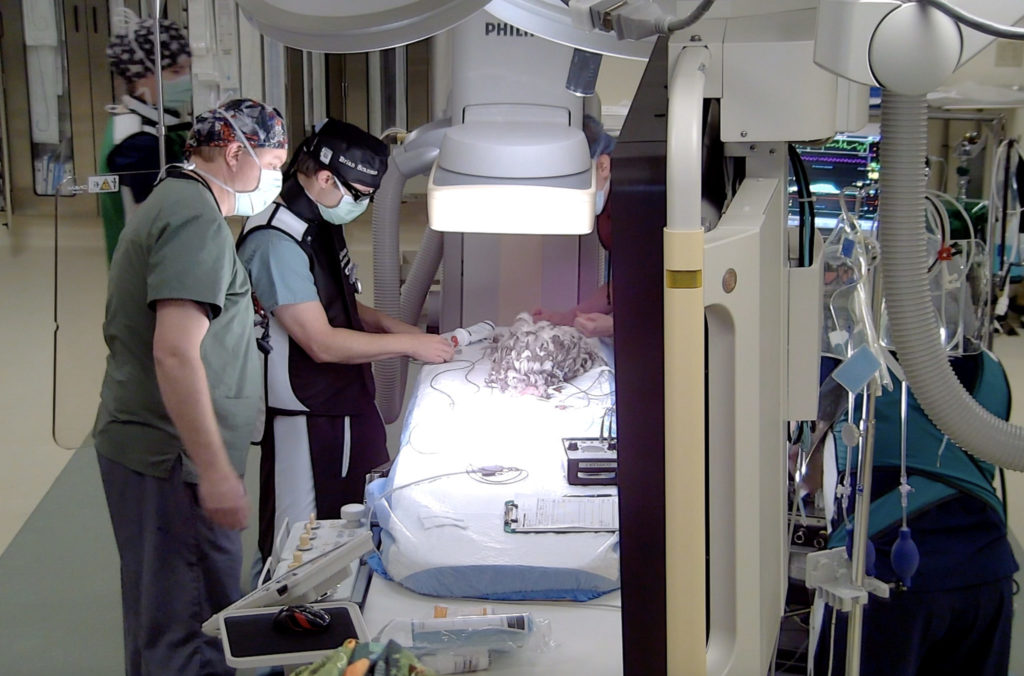

Though this is a fairly common procedure in dogs, it was the first in a chicken. Dr. Brian Scansen and the cardiology team passed a catheter through Blue’s jugular vein into her beating heart, and deployed an expandable occluder into the vessel to seal up the passage and restore normal blood flow.

“The patient had a heart condition that I believed I could fix and was cared for by a client that was brave enough to let us try. The species has no bearing on the care I provide; the goal of medicine is to hopefully cure and at least relieve symptoms of heart disease – be it a human, dog, cat, horse, bird, or reptile heart.” –Dr. Brian Scansen

Erin Allen, an amazing counselor from the hospital’s Argus Institute gave me regular updates through the surgery and celebrated with me over the phone when surgery was completed. Blue spent one night in the critical care unit and was able to go home with me the next evening.

Today, Blue knows nothing of her fame and contribution to the avian species. All she knows is that my husband and I cannot get over the healthy, bright red color of her comb and wattles. We smile every time she purrs with contentment as we stroke her soft feathers. We marvel at the little things too; like how she can drink water without sputtering or coughing, how bright and alive her eyes are, how talkative she is now, and how she again enjoys snuggling up close and burying her face into my neck.

Thinking back to that “chicken lady” nearly 20 years ago, I totally get it now and feel so guilty for my attitude about her chickens back then. I wish I could hug that woman around the neck and apologize in person. I guess karma got the last laugh on that one.

Now, the veterinary community knows it is possible to identify and repair a congenital heart condition in a chicken. They also know now that the value of a “barnyard” chicken can only be limited by the love, determination (and possibly a bit of insanity of a “mother hen”), the imagination and ingenuity of veterinary medicine, and the skill and knowledge of a group of world-class CSU veterinarians and staff.

Seleta Nothnagel is a “chicken lady” and medical laboratory scientist in clinical pathology for the CSU Veterinary Health System.