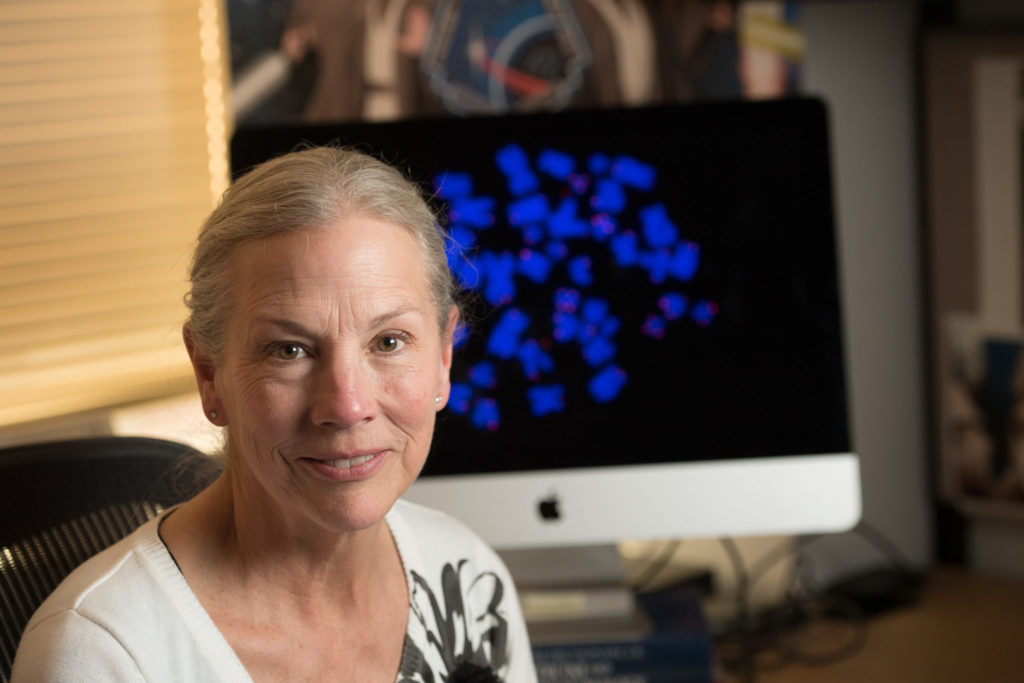

As part of the historic NASA Twins Study, Colorado State University Professor Susan Bailey published groundbreaking research on how spaceflight affects the human body. Now, Bailey, a radiation cancer biologist in CSU’s Department of Environmental and Radiological Health Sciences, is continuing to build on that work in a series of new papers out this week. The papers are part of the Space Omics and Medical Atlas package, or SOMA, which includes research published across multiple Nature journals.

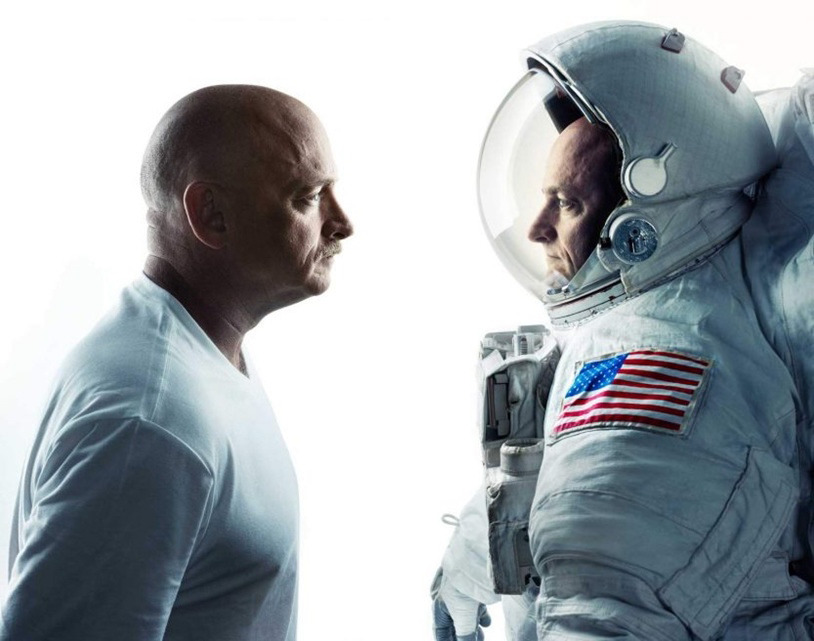

The 2019 Twins Study seized on a unique scientific opportunity. Astronaut Scott Kelly was slated to spend a year aboard the International Space Station, or ISS; at the same time, his identical twin Mark, a former astronaut and current U.S. senator representing Arizona, remained on Earth. Examining blood samples from the two astronauts before, during and after spaceflight, Bailey found that Scott’s telomeres — the protective “caps” at the ends of chromosomes, like a plastic tip that keeps a shoelace from fraying — got longer during his year in space.

Among other things, Bailey’s new work shows that telomere elongation occurred in four civilian astronauts who were part of the 2021 SpaceX Inspiration4 mission — a trip that lasted only three days.

“This was always an obvious question: How fast is the telomere response to spaceflight?” Bailey said. “That’s what was intriguing about the three-day mission. Same strategy. Same thinking. Let’s just see what it’s doing over three days. And in all four crew members we saw telomere elongation during spaceflight.”

In the earlier Twins Study, Bailey also observed that when Scott returned to Earth, the length of his telomeres rapidly decreased, and during his post-flight recovery they were generally shorter than they were before spaceflight. Three of the four astronauts on the Inspiration4 mission also exhibited rapid telomere shortening once they were back on Earth.

Telomere length, and, in particular, shortening, is a key molecular driver of aging and can also act as an indicator of age-related conditions such as dementias, cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Bailey has also examined samples from astronauts who spent six months in space. In a separate study, Bailey and team observed similar telomere length dynamics in a cohort of 10 astronauts on six-month missions onboard the ISS — elongation during spaceflight and rapid shortening upon return to Earth. In collaboration with fellow NASA Twins Study investigator Christopher Mason, a professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, they also previously found longer telomeres in twin mountain climbers who ascended Mount Everest while their non-climbing twins remained at lower altitude.

A second space age

Bailey’s new telomere findings are part of an expansive collection of space-related research released this week across a variety of journals and publications, including multiple Nature outlets. The SOMA package represents a collection that involves researchers at dozens of institutions producing scientific results from a diverse range of missions that included SpaceX Inspiration4 and others.

Significant increases in private, commercial and multi-national spaceflight during the past several years, together with technological advancements that have improved capabilities for evaluating human health effects of spaceflight, has marked a kind of second space age, according to the SOMA package. The authors, including Bailey, view this time as the beginning of a critical moment for research on space travel, and saw an opportunity to lay a foundation for other scientists to build on. Bailey said she hopes the collection will prompt others to ask new questions related to aerospace medicine and space biology.

“It’s been an amazing journey,” Bailey said. “This new collection really captured people’s imaginations and was exciting to be part of. My hope is to contribute in a way that’s going to somehow make a difference or make it possible for people to actually get to Mars.”

Another paper coming out in Communications Biology shows that the Insipiration4 crew — as well as Scott Kelly and the high-altitude climbers — exhibited increased levels of telomeric RNA, or TERRA. Those findings, along with additional lab studies, demonstrate that telomeric DNA is being damaged during spaceflight, Bailey said, potentially by radiation exposure. Bailey and Mason also provide a forward-looking research article about how telomeres and aging might inform the ability of humans to succeed at long-duration space travel or even the colonization of other planets.

Bailey contributed other work to the SOMA package. A paper published in Nature Communications led by Texas A&M researcher Dorothy Shippen, found that space-flown plants did not have longer telomeres during their time on the ISS. The plants, however, did show a significant spike in production of telomerase, an enzyme that helps maintain telomere length. The finding, Bailey said, suggests that plants — essential for long-term human survival in space — are perhaps more naturally well-suited to withstand the stressors of space than humans.

“We really tried to tie it all together,” Bailey said. “What have we learned and what is it going to take for people to not only survive, but to actually thrive and live in space or on other planets?”

CSU SOURCE spoke with Bailey more in-depth about the overall SOMA project and her new work.

Tell us about this new collection of research you’ve participated in.

There’s a special Space Omics and Medical Atlas (SOMA) package of papers being published across the Nature portfolio coming out on Tuesday. Everything you can imagine — from “multi-omics” to the microbiome and mitochrondrial function, physiology, cognition and telomere biology.

What does “omics” mean?

Omics is a general term — if you think of genomics, it just means sequencing the DNA. You can also sequence RNA — that’s transcriptomics. There’s epigenomics — changes that control which genes are turned on and off. Proteomics — identifying what proteins are made. Those kinds of things. And the idea of multi-omics is that we can look at combinations of omics-based results and ask, “What correlates with what?” Where can we identify pathways of what’s influencing what, and then get some mechanistic insight? For example, if telomere length changes, why is that happening? How is that happening? What is contributing to that? Can we turn to some of the omics data and say, “OK, what else changed during spaceflight, and what correlates with the telomere length changes we’re seeing?

What was the genesis of this new collection of space research?

It was really a strategy that was born out of what we did with the NASA Twins Study, because we started off with the main Science paper that came out with the basics of all the studies. But there was so much else with all the data that everybody had generated. After that, a whole series of companion papers came out across Cell. Now, a portfolio of papers across Nature and other publications contains additional studies and comparisons with the Inspiration4 crew. Chris Mason was a key player because he was working with some of the commercial providers. There was a real opportunity with SpaceX — a lot of these different research projects that were going to be happening around the crew — and he was able to jump on that. Chris had the bird’s eye view, realizing how much research there was, and he really put this into motion and made it happen. It’s been an amazing journey. This new collection really captured people’s imaginations, and it was exciting to be part of. My hope is to contribute in a way that’s going to somehow make a difference or make it possible for people to actually get to Mars one day.

What do you feel like the value is of collecting all this new research in one spot?

One of the papers highlights this whole idea that with the acceleration of commercial and private spaceflight and the technological advancements in “omics” based approaches for evaluating human health, we really are at the beginning of a second space age. We now have data repositories and sample repositories that researchers beyond us are going to have access to in the future and can do things with that we haven’t even thought about doing. I think that’s the really exciting part of this. The goal is to really enable long-duration human spaceflight and eventual habitation and colonization of other planets. That’s a mighty goal, and the weak link there is the person, or people. So, we really need to understand that impact on humans better. The commercialization aspect has changed everything; it’s no longer trained astronauts who have spent their whole lives training and are a perfect physical specimen of a certain age. As space tourism becomes more of a reality in the not-so-distant future, there will be individuals of different ages and health status.

What about some of the specific work that’s come out of your lab for this package?

The kind of research I’m involved with usually revolves around telomeres. The major criticism of the Twins Study was, of course, that there was an N of 1 — one astronaut, one ground control. We were fortunate in that we also had a separate cohort of 10 astronauts on six-month missions. We saw the same trends. Telomere elongation during spaceflight and a pretty dramatic and rapid decrease in telomere length when they came back. And even though telomere length recovered over the next six-to-nine months, astronauts overall had shorter telomeres after spaceflight than they had before. The Inspiration4 crew were all civilians, not trained astronauts. They were very different ages. Very different health status. One person was a childhood cancer survivor in her 20s. And we saw telomere elongation during a three-day flight. So now we have a much more complete timeline.

Did you want to ask this particular question, or did you get an opportunity to ask this particular question because of this three-day Inspiration4 mission?

A bit of both. This was always an obvious question. How fast is the telomere response to spaceflight? That’s what was intriguing about the three-day mission. Same strategy. Same thinking. Let’s just see if it happens within three days. And in all four crew members we saw telomere elongation during flight. And then when they came back to Earth three of the four showed a pretty dramatic decrease in telomere length.

So, you were able to test this in the three-day context but also to build evidence that this response happens regularly.

Across males, females, short duration, long duration, old, young, healthy, not-so-healthy. All these different individual variables are going to influence how a person responds. I can’t even tell you what a challenge it was at first. Nobody believed it. But at some point, you have to say, “This is a real response to spaceflight.” Now we’re seeing it in more individuals across various mission durations. And then of course the next step is mechanistic insight. Why is it happening? We’ve done some microgravity experiments; we don’t see telomere elongation with microgravity. So, we’re leaning much more toward chronic space radiation exposure.

Do you have any theories yet?

One of our favorite models is that radiation is killing lymphocytes, particularly those with short telomeres, because they’re very radiosensitive. So, you’re losing those. And then you’re continually spitting out more stem or progenitor-like cells into the circulation that have longer telomeres because they haven’t divided as much. So, part of the story could be an overall change in cell population dynamics. I think that makes a lot more sense than telomeres somehow “growing” in space.

How exciting is it to have another piece of the overall telomere-spaceflight picture?

It’s definitely exciting. The big idea is that we can use telomeres as valuable biomarkers of astronaut health during spaceflight, as well as for monitoring long-term health outcomes after they return. But it’s also really important when thinking about 24/7 radiation exposure in space because that’s a major hazard of spaceflight. Better understanding of the human health effects will help us figure out what we might be able to do about it. This could also help people on Earth, not only as radiation protectors are developed, but also as we progress with anti-aging research. As you think about long-duration spaceflight it really is an opportunity and kind of a new frontier for aging studies. We’re going to have to figure that out if we’re really going to spend long periods of time — years — not only during spaceflight but also living and reproducing in space and on other planets. So, I think, again, this SOMA project represents the foundation or beginning of futuristic thinking along those lines — not only for improving our healthspan on Earth but also for enabling people to thrive in space, and perhaps even ensuring the survival of humans.

College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

Improving the health of animals, people and the planet has been central to CSU’s land-grant mission since its founding, and that vision remains at the heart of the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences today. The College offers bachelor’s degrees in biomedical sciences and neuroscience and has a robust graduate student program, which includes the renowned Doctor of Veterinary Medicine program. CVMBS faculty explore a variety of pivotal issues in infectious disease, orthopedics, neuroscience, cancer biology, animal reproduction and translational medicine.