The National Institutes of Health has awarded a team of Colorado State University researchers $2.9 million to develop a new diagnostic platform needed to create a more accurate and user-friendly at-home HIV test, a product that could streamline an important treatment process for millions of patients.

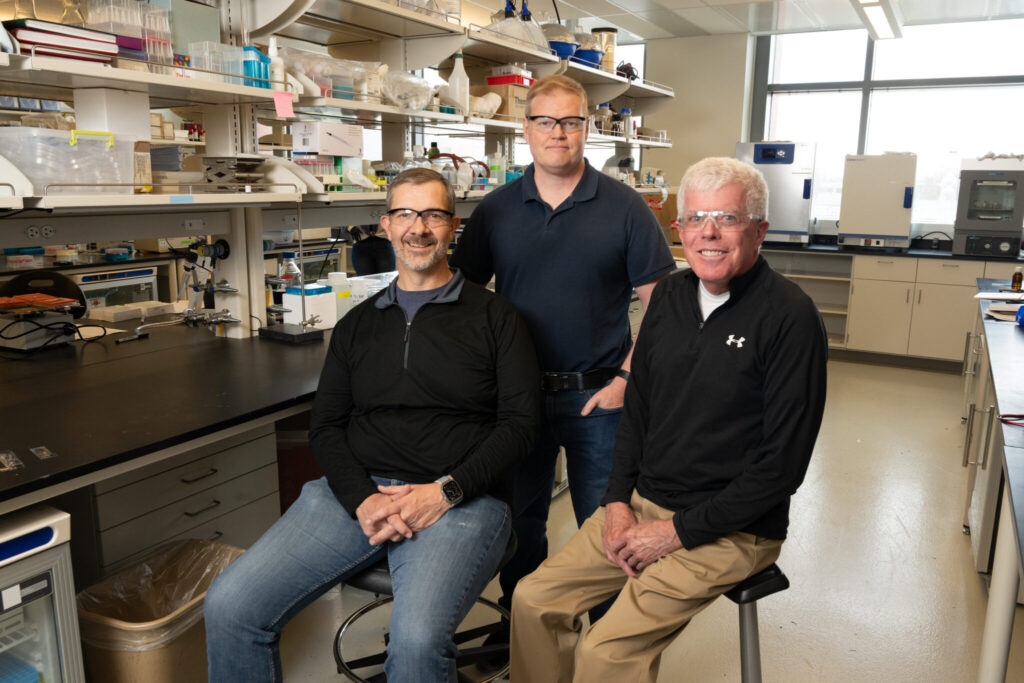

“As scientists, we’re always curious, we want to innovate new things, but this group has always wanted to take those things and apply them to the real world,” said principal investigator Brian Geiss, professor of microbiology, immunology and pathology in CSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

Approximately 1.2 million people in the U.S. and nearly 38 million worldwide live with HIV. About 62% of those patients receive an antiviral therapy known as Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, or PrEP. PrEP patients are required to undergo routine testing to ensure the virus in their bodies remains below detectable limits. Although rapid, at-home tests exist, they are relatively insensitive. What’s more, the tests don’t detect the actual virus; rather, they rely on identifying antibodies the body develops in response to the virus.

To get more accurate results, most patients are required to get a lab-run test at a clinic. That process, however, can be burdensome and time consuming.

Last year, the NIH solicited proposals for research that would contribute to a new rapid test or other tools for patients undergoing PrEP therapy. Led by Geiss, and in close collaboration with David Dandy and Chuck Henry, professors in CSU’s Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering and the Department of Chemistry, the group saw an opportunity. The team had been working on developing the scientific architecture for use in COVID-19 rapid tests and knew the same technology could be used to detect a viral protein produced by HIV.

“When we saw this call for proposals come out, it fit very well with the direction that our group was going in terms of developing the technology,” Geiss said.

The five-year NIH grant has two phases. The first, three-year phase will focus on continuing to develop the technology, building on the team’s existing COVID work and addressing any new challenges. For example, the HIV test will function with a finger prick like the glucose tests used by people who have diabetes as opposed to a nasal-swab style test. “We need to transition the devices over to detecting the virus protein in blood,” Dandy said.

Another obstacle, Dandy said, is that any design must still function after sitting on a drug store shelf for several months. “There are these things we absolutely have to work out, and it’s going to take a few years,” Dandy said.

The team will conduct the second, two-year phase of the project in partnership with Columbia University Medical School, which operates a clinic for HIV patients. The idea is to test the accuracy of a new device alongside the more established methods used in the clinic. It’s also an opportunity to make sure the device is intuitive and easy to use. “Sometimes researchers are totally locked into the academic world,” Dandy said. “You have to make sure you find out what people want and how they’re going to use it.”

Controlling the cost is another important element of the project. Geiss, Dandy and Henry are trying to develop laboratory-level performance in an at-home test while keeping the consumer price as low as possible. A lower cost device could help any eventual product be more applicable worldwide, Henry said.

“In a lot of the work I do I’m thinking about tools for global health,” Henry said. “I’ve been passionate about figuring out ways to develop diagnostic technology that can work in low- or middle-income countries where a lot of infectious diseases are a severe burden — from my perspective this is a continued growth of that work.”

Work on developing the diagnostic technology is already underway, Geiss said, and the team is excited by the project’s potential. “We really want to develop technologies that have an impact,” he said, “to translate our science into something that’s applicable in the real world.”