By Edith Silvas Villalobos

My brother, Denis Silvas, has now been dead longer than he was alive.

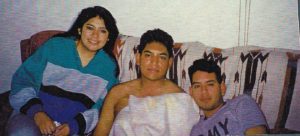

When Denis returned home from the Army, he still possessed a sharp sense of humor and a mischievous grin. His military training did not change his laid-back personality. He started college, loved going out in Italian silk shirts and Hugo Boss jackets, and ran daily.

One year later, while carrying an empty pizza box at his parttime job, he fell and broke his leg. Hours later, he was diagnosed with osteosarcoma (primary bone cancer). His leg had to be amputated. He was 23 years old and still covered under my parents’ health insurance.

According to my mother, as Denis was wheeled to surgery, the HMO representative told my parents they would have to pay for the surgery because this would not be covered by their insurance. That abrupt conversation catapulted our family down the slippery and thorny path of medical and financial unknowns. Later, my brother was transferred to the Audie L. Murphy Memorial Veterans’ Hospital to avoid interruption of treatment and care.

As one of two “youngsters” on the oncology ward at the VA Hospital, my brother stood out from the other patients for more reasons than his age. The revolving group of family and friends cast an eerie shadow of the backyard fiestas my parents threw – filling empty corridors with wafts of tacos, bursts of laughter, and intermittent dance beats like “Lookout Weekend” (Debbie Deb) and “Can You Feel the Beat” (Lisa Lisa & Cult Jam) blaring from his room.

The VA Hospital provided wonderful care to Denis, but as we met more cancer patients and their family members, I learned about the hardships they faced. VA patients, whose families could not be present because of travel expenses or job responsibilities, did not always have family support at the hospital. Some patients experienced language and cultural barriers. Others did not know how to access available resources, had mounting financial expenses, or like my parents, received denials for necessary treatment. It was not unusual for patients to face multiple compounded barriers. Collectively, we muddled words like 5-fluorouracil, thoracotomy, prognosis, and palliative care.

During what was supposed to be Denis’s last treatment appointment, the medical team discovered that his cancer had metastasized. Our celebration was paralyzed by grief. Four months after his 25th birthday, he passed away.

In Denis’s obituary, I wrote that he died after a two-year battle of “bone and lung cancer.” Years later, I realized that he died of bone cancer that had spread to his lungs. Not bone and lung cancer. It continues to upset me that my family and I never grasped the meaning of metastasis, nor was it explained in a way we could understand.

My parents both had graduate degrees, and Denis was insured, yet navigating the health care system while attending to Denis was challenging. I entered health care to help spare others the same struggles we experienced and witnessed. I have advocated for everyone to have access to care. This includes ensuring patients understand what they are told by eliminating language barriers and simplifying complex medical terms; proactively engaging historically marginalized and diverse communities in research on health disparities and why they persist; and identifying ways to maximize resources, reduce structural barriers, and disseminate key health messages. During the 20 years I worked in health care, I had the privilege to design, implement, and manage programs that continue to increase access to care for underserved communities and improve the overall equity of our health care system.

What began as a personal experience with my brother has been punctuated by the stories I have heard over the years. I am continually reminded that providing equitable care requires acknowledgment that no patient, family member, or caregiver is at the same juncture or has the same resources. There is no identical pace, path, cultural background, or belief system. Thus, it is imperative to seek remedies and provide care with cultural humility and respect.

Edith Silvas Villalobos is the diversity, equity, and inclusion coordinator for the One Health Institute. In this role, she is working to connect social justice and DEI work to advance the health of humans, animals, and the environment.