Coping with stress is critical for emotional and physical health.

Researchers from the lab of Brent Myers, associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, identified a neural circuit that connects directly from part of the prefrontal cortex known for processing environmental cues to part of the brainstem known for driving “fight or flight” stress responses and showed that activating it reduced stress responses in rats. Their results are published in The Journal of Physiology.

“It was very exciting to see that this pathway goes directly from the very front of the prefrontal cortex all the way down to the brainstem’s junction with the spinal cord,” Myers said. “It is a direct synapse from emotional and cognitive appraisal to physiological control that bypasses conventional circuitry.”

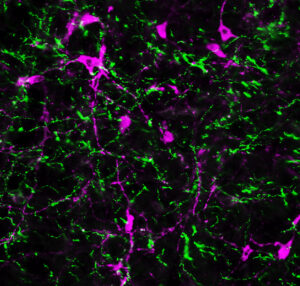

To carry out the study, the team stimulated the circuit using optogenetics, a technique that uses light to activate specific neurons. In driving that circuitry during stress, they saw that it reduced glucocorticoids and glucose stress responses.

“In trying to understand the exact mechanism of how this circuit reduces stress responses, we found where it acts on local inhibitory neurons inside the brainstem area that drives fight or flight responses,” said first author and recent biomedical sciences PhD graduate Sebastian Pace, now a postdoctoral researcher at the Salk Institute. “The inhibitory neurons act as a brake to stop the fight or flight stress response, so by activating it, those stress responses are reduced.”

Next, the lab plans to further investigate the function and necessity of this circuitry after chronic stress. “Seeing what this circuit does, and how important it is for health, has given us a lot of new knowledge to build from,” said Myers.