Chronic stress can lead to many health problems, including depression and cardiovascular disease. These conditions often occur in tandem and do so nearly twice as often in females than in males.

A new study by researchers from the lab of Brent Myers, associate professor in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, looks at how stress engages a prefrontal-hypothalamic circuit of the brain and impacts the stress response in rats. They found that stimulating this circuit relieved stress reactivity in males but not in females. Their results are published in Psychoneuroendocrinology.

“I’ve always been interested in how daily stress augments both mood disorders and cardiovascular disease,” said first author and recent biomedical sciences PhD graduate Derek Schaeuble, now a medical writer at PhiMed Communications. “And given the prevalence of depression and cardiovascular disease, it is very important to better understand how stress impacts this circuitry differently in males and females.”

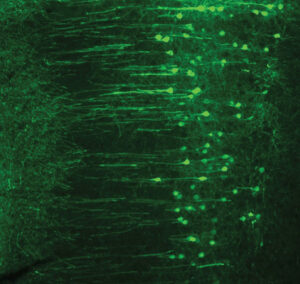

The lab previously found that the prefrontal-hypothalamic circuit, a brain circuit connecting the prefrontal cortex and the posterior hypothalamus, plays a key role in both cardiovascular and stress hormone responses. For this study, they stimulated the circuit to see how it impacted physiological stress responses and social and motivational behaviors using optogenetics, a technique that uses light to activate specific neurons. They found that doing so decreased the physiological stress response in males but not in females, and in some cases increased stress reactivity in females.

“It appears that this this circuit is critical for controlling an appropriate stress response and it does so very differently in males and females,” said Schaeuble. “Very few labs have the capacity to control neurocircuits and measure heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormone responses in real time to the precision and level taking place in the Myers lab.”

Because this circuit regulates stress physiology and behavior so differently in males and females, the team plans to further explore how chronic stress shapes the function of these synapses.

“These findings underscore the huge need for more research on female neuroscience and physiology,” said Myers. “For decades, this kind of work has only been done in males, so when we began to look at both sexes, we did not have much of a framework to work with or hypothesize from. Now that we have been finding almost completely opposite results in females, we have a lot more work to do.”